Give Students the Key With ‘Unlocking the Animal World’

Suggested grade levels: 4–6

Here are a just a few things that make the book Unlocking the Animal World and our accompanying materials essential resources for your classroom:

- Engaging informational text full of fascinating facts and stories about real animals

- Free class set of books

- Free accompanying worksheets on text features, text structure, main idea, summarizing, and inferencing

- Free accompanying chapter questions (literal, inferential, evaluative) with answer guide

Keep reading to find out more!

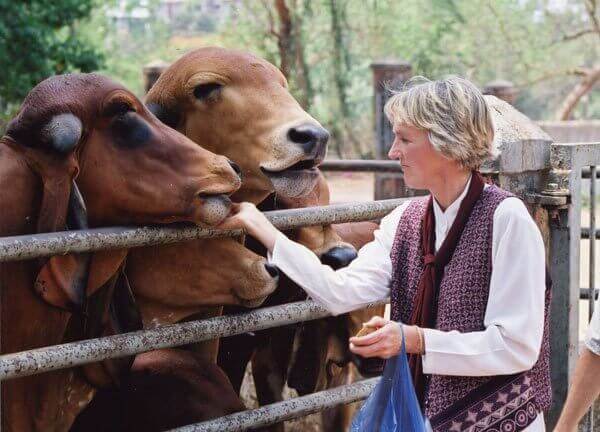

Unlock Student Engagement

Unlocking the Animal World: Incredible Facts and How Kids Can Be Superheroes for Animals by Ingrid Newkirk is a unique informational text about animals because it goes beyond discussing what they look like, what they eat, and where they naturally live. It distills years of research about animals’ lives into bite-size chunks of insight into remarkable discoveries that reveal animals as astounding individuals with intelligence, emotions, intricate communication networks, and myriad abilities. The text engages children with inspiring true stories and facts about animals’ lives, including that some fish create artwork and “sing” underwater, crows hold funerals, and gorillas play tag.

Unlock Empathy

This book incorporates a key element typically absent from classroom lessons about animals: how kids can help them! Teaching children that they can make a difference for animals by taking compassionate action is a powerful way to ignite academic learning, foster collaboration, and help students develop social-emotional skills.

Unlock SEL Competencies

According to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, the five core competencies of social and emotional learning (SEL) are self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. Activities that focus on compassion for animals can help students strengthen these competencies and shape them into responsible, critically thinking, and empathetic individuals. Here are some of the ways Unlocking the Animal World helps achieve that through the core SEL competencies:

Self-awareness

Self-awareness is the ability to accurately recognize one’s own emotions, thoughts, and values and how they influence behavior. “Kind Kids” boxes with multiple examples of kids’ empathy prompt students to relate those examples to their own experiences with others in various situations and to consider whether their actions align with their values.

Self-management

Self-management is the ability to successfully regulate one’s own emotions, thoughts, and behavior in different situations in order to achieve goals and aspirations. “Kind Kids” boxes, along with the chapter “How to Be a Hero for Animals,” give students the information they need to become inspired, have the courage to set goals, and take initiative.

Social awareness

Social awareness is the ability to understand others’ perspectives and empathize with them. By helping students see the world through the eyes of other animals, this type of perspective-taking can motivate them to have more empathy and compassion for everyone.

Relationship skills

Relationship skills are the ability to establish and maintain healthy and rewarding connections with others and effectively navigate different settings with diverse individuals. Helping students find a common cause in speaking out for animals can inspire them to work collaboratively and seek to communicate effectively in order to help all animals.

Responsible decision-making

Responsible decision-making is choosing to engage in caring and constructive personal behavior and social interactions based on ethical standards. This is cultivated by providing students with abundant information to help them make reasoned judgments and evaluate the consequences of their own actions with regard to the other sentient beings we share the planet with.

After students become fascinated by reading the chapters on animals’ journeys and how they communicate, love, work, play, and put family first, they’ll be riveted on the next chapter, which is about the seemingly endless types of careers they can pursue to help animals, followed by the compelling finale, “How to be a Hero for Animals.” When kids learn about the countless ways in which animals are exploited and suffering in today’s society and that there are ways they can help them, their motivation to learn more about how to do that skyrockets and they’re eager to roll up their sleeves and take action. You’ll see them enthusiastically read, write, collaborate, and speak publicly—all to get the message out about helping animals—finding common cause with their classmates and building community within the classroom and the school.

Unlocking the Animal World taps into children’s natural affinity for other animals and incorporates information about ways to help them, unleashing students’ creativity, ingenuity, and even their entrepreneurial spirit to make the world a better place for all.

Unlock Academic Motivation

As we see time and again, encouraging kids to follow their passion to help animals fuels their academic fire and gives them an authentic reason to do the following:

- Read. Students, including those identified as frustrated or reluctant learners, want to learn more about animal-related issues that resonate with them, which inspires them to find out what else is going on in the world.

- Write. Once students grasp the idea that their message about helping animals must be clearly written so that others will understand it, they’re eager to edit and revise their writing painstakingly, which they’re otherwise often reluctant to do.

Reading texts about animal protection can have a positive effect on standards-based student academic performance. One study showed that students who read passages on animal protection not only achieved better results overall but also succeeded much better on questions addressing specific Common Core Reading for Information standards. This increased performance level is likely explained by young people’s enhanced attentiveness to stories about kindness to animals.

How to Get Started

Request your free class set of books here. Yes, your students can all have their own copy of the book!

Get Kids Excited to Read: Preview Unlocking the Animal World

Students can use various text features to preview the book. They can look at the table of contents, headings, illustrations, fact boxes, and more to identify the topic and get an idea of what they’ll learn about. You can also use the Scavenger Hunt for Text Features worksheet to help them with their preview.

You can also get your students excited about the book by reading the tantalizing excerpts listed below aloud and then showing videos about each fact or story to enhance the reading (many of the facts and stories in the book can be looked up on YouTube).

- Page 31: Wounda the chimpanzee hugging Jane Goodall

- Pages 32–33: Best friends Tarra the elephant and Bella the dog

- Pages 35–36: Laysan albatross couple’s dance

- Page 71: Crows sled down snowy roofs

Feed Two Birds With One Scone

Here are some suggestions on how to use this book in your classroom to meet academic requirements and foster empathy simultaneously:

- Allow students to read the book during independent reading time.

- Assign chapters to read for homework along with literal, inferential, and evaluative comprehension questions. (See below for chapter questions and an answer key.)

- Use these worksheets in conjunction with selected passages from the book to help students practice identifying text structure, determining the main idea, summarizing, and inferencing.

You can use the book as a mentor text for informational writing, which will show students that research-based writing can be vivid, memorable, stylish, and full of personality. You can also let students choose a particular topic or type of animal as a subject for further research. Additionally, you can assign a reading response activity, such as one of the following:

- After students read a chapter, have them complete the statements “Something I already knew was …” and “Something new I learned was …”.

- After students read the book, have them write a letter to the author about something they would still like to know more about. (See below for how to get in touch with the author.)

The following questions, along with the worksheets, will promote critical thinking about the information presented in the book and help students practice important skills, such as determining the main idea, inferencing, summarizing, and analyzing text structure.

The following learning standards are addressed:

Grade 4

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.1

Refer to details and examples in a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.2

Determine the main idea of a text and explain how it is supported by key details; summarize the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.5

Describe the overall structure (e.g., chronology, comparison, cause/effect, problem/solution) of events, ideas, concepts, or information in a text or part of a text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.4.8

Explain how an author uses reasons and evidence to support particular points in a text.

Grade 5

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.5.1

Quote accurately from a text when explaining what the text says explicitly and when drawing inferences from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.5.2

Determine two or more main ideas of a text and explain how they are supported by key details; summarize the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.5.5

Compare and contrast the overall structure (e.g., chronology, comparison, cause/effect, problem/solution) of events, ideas, concepts, or information in two or more texts.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.5.8

Explain how an author uses reasons and evidence to support particular points in a text, identifying which reasons and evidence support which point(s).

Grade 6

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.6.1

Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.6.2

Determine a central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.6.5

Analyze how a particular sentence, paragraph, chapter, or section fits into the overall structure of a text and contributes to the development of the ideas.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.6.8

Trace and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, distinguishing claims that are supported by reasons and evidence from claims that are not.

Chapter Questions for Reading Comprehension

Introduction

- Why did researchers test Kandula the elephant by giving him a stick to knock the fruit down? Why wasn’t he interested in the stick? (Literal)

- What is biomimicry? Describe some examples. (Literal)

Chapter 1: ‘Daring Journeys’

- What objects and gadgets do humans use to get from one place to another? (Literal)

- (a) What evidence does the author use to support the claim that animals make daring journeys? (Literal)

(b) Is the evidence convincing? Why or why not? (Evaluative) - Scientists think birds are able to make such long trips to specific locations by “reading” the Earth’s magnetic field, using the sun and stars as a giant sky map, or creating sound maps that help them “hear their way home.” Which explanation do you think is most probable, and what makes you think so? (Evaluative)

- Describe the Great Migration. (Literal)

- Which fact surprised you the most? Why? (Evaluative)

- Why do you think that after Klepetan the stork flies 5,000 miles to spend the winter in South Africa with other storks, he returns every spring to Malena, who can’t fly anymore? (Inferential)

Chapter 2: ‘Animal Voices’

- What are some ways animals communicate? (Literal)

- Why was Stella the dog’s choice to press the buttons “love you” and “no” when she couldn’t get her guardian Christina’s attention so impressive? (Inferential)

- Were you surprised to learn that some fish “shout” or use tools like oyster shells to “amp up their volume”? Why or why not? (Evaluative)

- Why do birds sing? (Literal)

- Why do you think birds who live in people’s homes are often lonely? (Inferential)

Chapter 3: ‘Love and Friendship’

- How did Wounda the chimpanzee show Jane Goodall that she loved her? (Literal)

- Why do you think Tarra and Bella became friends? (Inferential)

- How does it make you feel to know that the stallion being loaded into a trailer during a wildfire would risk his own life to lead the mare and her filly to safety? Why? (Evaluative)

- Did it surprise you to learn that rats and rhesus monkeys would rather go without food than give someone else an electric shock? Why or why not? (Evaluative)

Chapter 4: ‘Family First’

- How do leeches care for their family? (Literal)

- Why do you think exploding ants give up their lives to defend their colony? (Inferential)

- Mother hens teach their babies how to communicate when they’re still inside their shells. What is your opinion on hatching baby chicks in incubators without their mothers? (Evaluative)

Chapter 5: ‘Let’s Get to Work!’

- What do cleaner wrasse fish do in their “cleaning stations”? (Literal)

- What kinds of things do groups of elephants and African wild dogs do that are similar to how you interact with classmates or friends? (Inferential)

- What steps do crows in Japan take in order to obtain a walnut treat? (Literal)

- Why do you think Sid and Inky the octopuses wanted to escape from aquariums? (Inferential)

- How did it make you feel to learn that leafcutter ants carry leaves that weigh much more than they do in order to grow a special fungus in underground gardens? Why? (Evaluative)

Chapter 6: ‘Let’s Play!’

- What did researchers learn were the reasons that most—or maybe all—animals like to play? (Literal)

- Mother animals, like mother deer, watch over and guide their babies as they learn to play, which helps them build muscle and learn important life skills. How do you think baby animals are affected when they’re taken away from their mothers? (Inferential)

- Were you surprised to learn that sharks like to play? Why or why not? (Evaluative)

- What is one way crows like to play? (Literal)

Answers to Chapter Questions for Reading Comprehension

Introduction

- Why did researchers test Kandula the elephant by giving him a stick to knock the fruit down? Why wasn’t he interested in the stick? (Literal)

Answer: For centuries, humans judged the intelligence of other animals based on how well they could do the things humans are good at. Kandula knew that if he wrapped his trunk around the stick, it would prevent him from smelling, feeling, and grabbing the fruit. - What is biomimicry? Describe some examples. (Literal)

Answer: Biomimicry is when humans copy nature to solve problems. For example, the first airplane designs were based on observations of how birds take off, soar through the air, and land. Later, airlines learned how to get passengers on and off planes faster by observing ants, who are masters of cooperation. The idea for drinking straws came from watching butterflies, who insert a long, round part of their mouth into flowers to suck up nectar. Bike helmets imitate turtles’ protective shells. Swim fins are similar to ducks’ webbed feet. And suction cups were developed to be like the suckers on octopuses arms, which they use to grip objects tightly.

Chapter 1: ‘Daring Journeys’

- What objects and gadgets do humans use to get from one place to another? (Literal)

Answer: We use GPS, red, yellow, and green stoplights, and signs on streets and buildings. - (a) What evidence does the author use to support the claim that animals make daring journeys? (Literal)

Answer: Sea turtles find their way through vast oceans by orienting themselves along the north-south lines of the Earth’s magnetic field. They can find their way back to the exact beach where they were hatched to lay their own eggs, even many years later and from thousands of miles away.

Ants who live in the desert can’t look for familiar plants and trees to find their way home, so when they leave the nest, they count their steps. They also keep track of their turns, their speed, and how much time has passed. Then they use math to figure out the fastest way back.

Small white birds called Arctic terns would fit in the palm of your hand, but they fly all the way from the North Pole to the South Pole every year, which is almost 12,500 miles. Arctic terns hold the world record for the longest annual migration. Out of all the animals who move to a different area of the world for part of each year (usually because of weather), these tiny, tough birds go the farthest.

Klepetan the stork makes a 5,000-mile trip to South Africa every winter. He stays in his wintering spot with other storks, and on the exact same day every spring, he returns to the same roof to see Malena.

During World War I, a pigeon named Cher Ami saved the lives of 194 American soldiers who had been separated from the rest of the troops. He flew 25 miles in just 25 minutes to carry a message to the people who could rescue them. He continued flying even after being shot twice.

Western gray whales (who can grow to 50 feet long) travel up to 10,000 miles a year.

Pacific salmon hatch in freshwater streams in the Northwest region of the U.S. They adapt to saltwater and head out into the ocean to find food and grow larger and stronger. Rivers flow toward the ocean, so to return home, these fish have to fight against the current the whole way. Their journey is often several hundred miles.

Bees can return to their hives even after being trapped inside a car and driven miles away.

Each year, 200,000 zebras, 400,000 gazelles, and more than 1.5 million wildebeests make a 500-mile trek in a giant circle. This is known as the Great Migration.

(b) Is the evidence convincing? Why or why not? (Evaluative)

Possible answer: The evidence is convincing that animals make daring journeys. They travel long distances and still find their way back to exact locations. And a pigeon shot twice during a war still managed to fly to his destination, which saved lives. - Scientists think birds are able to make such long trips to specific locations by “reading” the Earth’s magnetic field, using the sun and stars to create a giant sky map, or creating sound maps of areas that help them “hear their way home.” Which explanation do you think is most probable, and what makes you think so? (Evaluative)

Possible Answer: I think sound maps are the most probable explanation because I can imagine listening to sounds to help me find my way to a destination. - Describe the Great Migration. (Literal)

Answer: The Great Migration is the largest migration of land animals on Earth. Each year, 200,000 zebras, 400,000 gazelles, and more than 1.5 million wildebeests make a 500-mile trek in a giant circle. They follow the seasonal rains as they fall on the eastern coast of Africa in order to eat the lush green grass. Most of the migration occurs in the Serengeti, a large natural area that has forests, plains, rivers, hills, and swamps. - What fact surprised you the most? Why? (Evaluative)

Possible answer: I was surprised to learn about the Great Migration. I’ve never heard of that before, and it’s really amazing that so many animals all make this journey together. - Why do you think that after Klepetan the stork flies 5,000 miles to spend the winter in South Africa with other storks, he returns every spring to Malena, who can’t fly anymore? (Inferential)

Possible answer: Like many birds, Klepetan flies south for the winter and comes home in the spring. Storks choose only one mate, and Klepetan and Malena have been together for most of their lives. They are family and love each other, so it makes sense that he would return to be with her every spring.

Chapter 2: ‘Animal Voices’

- What are some ways animals communicate? (Literal)

Answer: Animals such as chimpanzees communicate using body language, including gestures and facial expressions. Mice sing. Dogs use particular barks, yaps, whines, howls, and growls to communicate.

Cats create specific meows to name their guardians. They rub against your legs or wrap their tail around you to say “hello” and give you a hug. Also, slow blinking is how cats smile at us.

Frogs and toads use whistles, chirps, croaks, ribbits, clucks, peeps, grunts, and even barks to communicate. Some frogs dance to communicate as well.

Dolphins use distinct whistles and sounds in speech patterns similar to those of humans.

Humpback whales can produce songs that are so complex that it takes a trained musician to truly appreciate them.

Some fish shout and hum loudly.

Birds sing to share information with their partners, young, and flockmates.

Animals may not always speak in ways we can easily understand. But they exchange information with each other constantly. - Why was Stella the dog’s choice to press the buttons “love you” and “no” when she couldn’t get her guardian Christina’s attention so impressive? (Inferential)

Possible answer: Stella the dog learned how to communicate using human vocabulary on a special keyboard used with children who need help with speech. It has buttons on it that each play one word. Since dogs communicate differently than humans, it’s impressive that Stella not only learned what individual words on the keyboard meant but also was able to put them together to communicate how she felt. - Were you surprised to learn that some fish “shout” or use tools like oyster shells to “amp up their volume”? Why or why not? (Evaluative)

Possible answer: I was surprised to learn that fish “shout” or use tools because I thought only humans could do that. - Why do birds sing? (Literal)

Answer: Birds sing to share information with their partners, young, and flockmates. - Why do you think birds who live in people’s homes are often lonely? (Inferential)

Possible Answer: A team of scientists realized that birds who live in people’s homes are often lonely. In their natural habitat, birds live with their flocks, so they can fly and play together. In nature, they’re surrounded by others of their own kind, so when they live with only humans, it can be lonely for them.

Chapter 3: ‘Love and Friendship’

- How did Wounda the chimpanzee show Jane Goodall that she loved her? (Literal)

Answer: She hugged her. - Why do you think Tarra and Bella became friends? (Inferential)

Possible answer: Bella and Tarra liked each other instantly. They went for long walks, played, and ate together and slept next to each other. When she was homeless, Bella was alone and didn’t have any friends. Dogs and elephants both like to have friends. Sometimes individuals who appear to be very different from each other actually have a lot in common. Even though Tarra and Bella were different types of animals, they liked to do the same things, such as going for walks and playing, and they enjoyed being together. - How does it make you feel to know that the stallion being loaded into a trailer during a wildfire risked his own life to lead the mare and her filly to safety? Why? (Evaluative)

Possible answer: It makes me feel happy to know that the mare and her filly were saved, because I don’t want animals to get hurt. It’s good to know that animals will help one another when they can. - Did it surprise you to learn that rats and rhesus monkeys would rather go without food than give someone else an electric shock? Why or why not? (Evaluative)

Possible answer: It surprised me because I thought these animals would want their food no matter what, even if it hurt others.

Chapter 4: ‘Family First’

- How do leeches care for their families? (Literal)

Answer: Adult leeches take great care of their young as they grow. They shuttle them from safe place to safe place and protect them from danger. - Why do you think exploding ants give up their lives to defend their colony? (Inferential)

Possible answer: When an intruder tries to attack their colony, exploding ants defend it by making themselves explode, spraying the invader with sticky, icky fluid from sacs on their bodies and saving the day. Their colony is like their family, so they’re willing to do whatever it takes to protect it, even if that means they’ll die. - Mother hens teach their babies how to communicate when they’re still inside their shells. What is your opinion on hatching baby chicks in incubators without their mothers? (Evaluative)

Possible answer: I think baby chicks should always be with their mothers—otherwise, they won’t receive valuable information that only mother hens can provide, such as how to communicate.

Chapter 5: ‘Let’s Get to Work!’

- What do cleaner wrasse fish do in their “cleaning stations?” (Literal)

Answer: They clean larger fish’s teeth and mouths. They do this by swimming inside and using their own mouths to gently nibble away anything that shouldn’t be there. This provides cleaner wrasses with food and helps the larger fish stay healthy. Larger fish and even turtles line up to have their teeth cleaned. - What kinds of things do groups of elephants and African wild dogs do that are similar to how you interact with classmates or friends? (Inferential)

Possible answer: Elephant herds talk things over and take turns sharing their thoughts. When a plan succeeds, they celebrate by giving each other a “high-five” with their trunks. I take turns with my classmates when we’re discussing something, and we give each other high-fives, too.

African wild dogs signal to the rest of their pack that they’d like to go look for food by sneezing. Other dogs sneeze if that’s what they want to do, too. If they’d rather rest, they don’t sneeze. When I’m with my friends, we sometimes gesture to each other to signal when we want to do something. - What steps do crows in Japan take in order to obtain a walnut treat? (Literal)

Answer: Crows line up with people who are getting ready to cross the street. When the cars stop, the birds dart into the crosswalk and put walnuts in front of them. Then they race back to the sidewalk. As the cars drove over the walnuts, they smash the shells, revealing the tasty nuts inside. When the cars stop again, the crows run out and gobble up their treats. If any of the walnuts aren’t broken open, the crows move them a little and try again. - Why do you think Sid and Inky the octopuses wanted to escape from aquariums? (Inferential)

Possible answer: Sid kept escaping from a tank and even spent five days hiding in a drain. Finally, the staff understood that they should set him free. Inky climbed out of a tank, scooted across the floor, and slid down a drainpipe that dropped 164 feet—all the way to the open sea! In aquariums, octopuses are forced to live in tanks, but all sentient beings want to live free. - How did it make you feel to learn that leafcutter ants carry leaves that weigh much more than they do in order to grow a special fungus in underground gardens? Why? (Evaluative)

Possible answer: I was amazed, because I have seen leafcutter ants carry leaves but just assumed they were going to eat them. I had no idea they used them to create gardens underground.

Chapter 6: ‘Let’s Play!’

- What did researchers learn were the reasons that most—or maybe all—animals like to play? (Literal)

Answer: Animals play for the same reasons humans do. Playing is fun and can help us learn important skills. - Mother animals like mother deer watch over and guide their babies as they learn to play, which helps them build muscle and learn important life skills. How do you think baby animals are affected when they’re taken away from their mothers? (Inferential)

Possible answer: As baby animals play, they get stronger and more coordinated. They also learn how to balance and defend themselves. All baby animals need their mothers, and without them, they might not learn these important skills to help them in life. - Were you surprised to learn that sharks like to play? Why or why not? (Evaluative)

Possible answer: I was surprised to read that sharks like to flip and spin around in long pieces of seaweed that grow from the ocean floor. That reminds me of things I’ve seen dolphins do. I’ve heard that sharks are mean, so I never thought of them as being playful, but it makes sense since they’ are living beings, too. - What is one way crows like to play? (Literal)

Answer: Crows like to go snowboarding by using plastic lids like sleds on snowy roofs. They pick up a lid with their beaks and fly to the top of a roof they like. Then they set the lid down, hop onto it with both feet, and slide all the way down the roof. Then they do it all again.

Worksheets

Download each worksheet here, or as a bundle on TPT.

Text Features

Students can complete the Scavenger Hunt for Text Features worksheet to help them understand and use those parts of the text to improve their comprehension.

Text Structure

Students can read the “Let’s Get to Work!” passage and complete the Text Structure worksheet to help them understand how the author organized the information in the text and help them focus their attention on key concepts, anticipate what is to come, and monitor their comprehension as they read the full text.

Determine the Main Idea

Students can read the “Family First” passage and complete the Main Idea and Supporting Details worksheet to practice foundational skills for comprehension. This will help them understand the points the author is making in the book.

Summarizing

Students can read the “Woof and Wow!” passage and write a three- or four-sentence summary of it. This will help them practice determining essential ideas and consolidating important supporting information.

Inferencing

Students can read the “Love Isn’t Just for Humans” passage and complete the Making Inferences: “Love Isn’t Just for Humans” worksheet. This will help them gain a deeper understanding of the text by practicing how to make inferences. They’ll engage in the process of using evidence and reasoning to reach conclusions by combining their existing knowledge with new information.

Check out TeachKind’s Unlocking the Animal World kahoot!

After Completing the Book

You can wrap up by discussing the book as a whole and posing the following questions:

- What was your favorite part? Why?

- Did you learn anything new? If so, please explain.

- Was there anything you didn’t understand? If so, please explain.

- Is there anything discussed in the book that you’d like to learn more about?

- Did anything you read remind you of something in your own life or that you’ve seen?

- Would you recommend this book to a friend? Explain your reasons.

Questions for the Author

Students will have the exciting opportunity to send questions to the author of Unlocking the Animal World, by Ingrid Newkirk. After they’ve read the book and completed the activities above, they can prepare questions for her about the book, why she wrote it, animal rights, or anything else they’d like to know. Then, send the questions to [email protected].

Real-World Connection

Reading the chapter “How to Be a Hero for Animals” will likely spark students’ interest in taking compassionate action for animals. Sometimes when students are free to follow their passion and brainstorm ways to help animals on their own, they come up with ideas that teachers could never have imagined. For example, one group of fifth grade students came up with the idea of selling pickles to help dogs in their local animal shelter—because they were “in a pickle”!

You can also help students brainstorm a list of actions they could take within their own school or community that would help animals. Then they’d choose the one action they’re most passionate about, form a group with other students who share the same enthusiasm, and create a plan to carry it out.

Students can make posters, create videos, write letters to officials, start petitions, attend town hall meetings, etc., to engage with an issue they’re passionate about. Here are some ideas for how students can channel their empathy into inspirational action to help animals:

- Organize a supply drive for your local animal shelter.

- Get your school to ban glue traps on campus.

- Host a cruelty-free fashion show.

- Get your school to introduce (or add more!) vegan options in the cafeteria.

Students aged 12 and under can also become members of PETA Kids’ free Kind Kid program. They’ll receive an official membership card and monthly e-mails with an activity they can do to help animals, like making toys for cats at their local animal shelter.

As you guide students through the process of thoughtful collaboration with their peers, you’ll see their natural love of animals inspire them to develop skills in reading, writing, public speaking, and more, just like these middle schoolers whose campaign to ban puppy mills sprang from a school project. They created fliers, public service announcements, petitions, and more while honing a long list of academic skills simultaneously.

Additional Resources for Students

- PETAKids.com (for children aged 12 and under)

- Join the Kind Kid program

- Animal Facts

- How to Go Vegan: A Kid’s Guide

Like these ideas? Please share them with other teachers and encourage them to incorporate compassion for animals into their literacy lessons.

Need more classroom inspiration? Fill out the form below to sign up for e-mails from TeachKind: