TeachKind’s Guide to Addressing Problems in Some Popular Children’s Books

Let’s be real—the world isn’t yet the vegan utopia that we strive for, and the literature we teach our students often reflects that less-than-ideal state. While there are a number of humane children’s books with messages of compassion, empathy, and inclusion, many classic tales as well as modern texts are rife with questionable language and themes that depict animals as willing participants in their own suffering, or worse, as martyrs for the entire nonhuman animal kingdom. So what’s a humane educator to do?

There’s no need to replace your entire classroom library. You can still teach kindness using problematic materials. In fact, we encourage it. It’s important for your students to have access to a variety of literature—and it gives you an opportunity to point out problems with the ways that people often communicate about animals. Use TeachKind’s guide to address these issues in some of the most commonly taught stories in schools, and make “teachable moments” out of tales whose messages are at odds with the animal rights movement.

Set Kind Standards From the Beginning

While many children naturally harbor an innate sense of compassion for animals, it can be challenging to “un-teach” lessons that have been reinforced since birth. That’s why laying the groundwork for compassion early in the school year is so important—starting with the words that we use.

Unfortunately, many of us—children’s book authors included—grew up hearing and using common language conventions that perpetuate the “othering” of animals. For example, referring to an animal as “it” suggests that the animal is an inanimate object rather than an individual with thoughts and feelings. Many authors do this, so when you’re reading with your students, you may come across it. Encourage students to point out when an author has made this error and to practice using the personal pronouns “he,” “she,” and “they” in their various forms when talking about animals.

Similarly, referring to people as animals in a derogatory manner—such as calling a cowardly person a “chicken,” a dishonest person a “snake,” a gluttonous person a “pig,” and so on—isn’t only hurtful but also sends students the dangerous message that nonhuman animals are inferior to humans. While these phrases may seem harmless and are used figuratively, they carry a deeper meaning that can send undesirable signals to students about the relationship between humans and other animals and can normalize abuse. If you come across an anti-animal phrase in your reading, have students consider what the author meant and remind them that it’s never okay to hurt anyone, including animals.

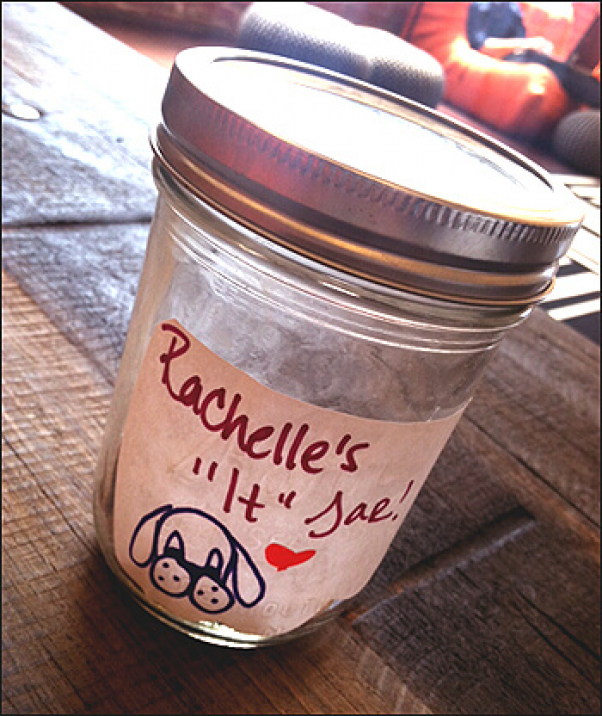

Teaching students to use animal-friendly language can cultivate positive relationships among all beings and help end the epidemic of youth violence toward animals. Try keeping an “It” Jar and using TeachKind’s animal-friendly idioms posters to discourage the use of anti-animal language in your classroom.

Ask Questions

Rather than telling your students that it’s wrong to exploit animals, allow them to come to that conclusion on their own by asking a series of thought-provoking questions while reading questionable texts. Take the classic children’s book series Curious George, for example. Many children grew up identifying with this mischievous chimpanzee and following him on his big-city “adventures,” but his story inadvertently promotes the imprisonment and exploitation of animals who belong in their natural habitats. By glossing over the fact that he was taken from his home in Africa by “the man with the yellow hat,” we fail to teach students that all individuals—no matter their species—deserve freedom, respect, and compassion.

As you read these stories with your students, remind them that while George is just a character in the books, in reality, many chimpanzees and other animals aren’t allowed to live in their natural habitats or do anything that’s natural and important to them. They’re kept as “pets” or exploited by the entertainment industry. Explain that while the man with the yellow hat may appear to love George very much, wild animals are happiest and healthiest in their natural habitats. Use the following tips to guide students in thinking about animal exploitation as you read other questionable texts:

- Ask them, “How would you feel if you couldn’t run and play with your friends, eat your favorite foods, or spend time with your family? How would you feel if you could never leave your house or even your bedroom?”

- Discuss an act of abuse in the story and ask, “Would you do that to your brother or sister, one of your classmates, or your animal companion at home? Why not? Should we do it to other animals? Why not?”

- Ask students how they think animal characters who endured abusive acts felt.

- Point out that we know what the animals in the story are feeling because they can talk, and ask how we can figure out what real animals are feeling.

- Ask, “What should you do in real life if you see an animal who is hurt or lost?”

- Ask students what human characters in the story could have done differently to be kinder to the animal characters.

Empower the Individuals

After explaining to students why a text is problematic, share with them all the ways they can help animals in their own lives by choosing not to eat them, avoiding forms of entertainment that exploit them, shopping cruelty-free, and so on. For example, when talking about Curious George, remind students that wild animals like chimpanzees, birds, reptiles, and fish don’t make good companions and are happiest and healthiest when left in their natural habitats. Also, discuss the ways in which animals are used in entertainment, and have your students pledge never to visit circuses, roadside zoos, marine parks, or other places that hold animals captive. Take your class on a virtual field trip, visit your local open-admission animal shelter, or watch a movie that uses computer-generated imagery instead of animals.

Below, we’ve listed other popular children’s books with problematic messages, along with tips on using them for teachable moments.

Companion Animals

In Stone Fox, by John Reynolds Gardiner, protagonist Little Willy and his dog, Searchlight, enter the National Dogsled Race in an attempt to win the $500 prize to pay his ill grandfather’s back taxes.

Dogsledding is a cruel industry in which dogs are forced to run long distances while pulling heavy sleds in extreme weather conditions. The deadly Iditarod, for example, has resulted in the deaths of more than 150 dogs since it began in 1973, including five who died during a single week of the 2017 event.

Ask students to think about races that they might run during recess or gym class. Ask them, “Do you like to run?” and “Would you like to run 1,000 miles in the snow?” Explain that even though many dogs also like to run, when they’re forced to participate in races, they sustain injuries and suffer from illnesses, and their needs for shelter and love aren’t met. Remind students that there’s a huge difference between having fun in the snow with your animal companion at home and forcing dogs to participate in deadly races like the Iditarod. Urge them never to attend dog-sledding races. To supplement this text, read TeachKind’s comic book A Dog’s Life.

Other books with poor messaging about animal companions include A Home for Dixie by Emma Jackson (the dog is crated at night), Meow Means Mischief by Ann Whitehead Nagda (a family sprays a kitten in the face with a water gun to “train” her), and Straydog by Kathe Koja (a character kills exotic “pet” fish, and stray dogs are described as “lucky” and “free”).

Animals Used in Entertainment

The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate is about a silverback gorilla named Ivan who lives in a cage at a mall with other captive animals, including some who are forced to perform in a circus. Through his artwork, which his owner sells, Ivan communicates to mall patrons that he and his friends wish to live in a zoo, and after a public outcry, the animals are transported to one.

Sadly, animals born in captivity usually can’t be released into nature, because they haven’t learned the essential skills needed to survive in the wild. In Ivan’s case, an accredited zoo was the best option, because it gave him the opportunity to enjoy the company of other gorillas, be cared for by expert staff, and be provided with veterinary care as well as a robust environmental enrichment program that allowed him to engage in his natural behavior. But even the best artificial environments can’t come close to providing the space, diversity, and freedom that animals want and need. Be sure to have a broader conversation with students about this complex issue.

Animals in roadside zoos and pseudo-sanctuaries are forced to spend their lives behind bars just to entertain the public. Their living conditions are often dismal, with animals confined to cramped, filthy, barren enclosures.

Discuss with students the differences between roadside zoos and accredited sanctuaries. View live-camera footage of elephants and other rescued animals living peacefully in expansive landscapes rather than in cramped, dirty cages, where they have no respite from the constant gaze of humans. Make sure that students know the best way to help animals used in entertainment is to boycott all facilities that profit from this exploitation. To supplement this text, read TeachKind’s comic book An Elephant’s Life and A Tiger’s Life.

Another book with poor messaging about animals used in entertainment is Good Night, Gorilla by Peggy Rathmann, which depicts animals living in barren cages.

Animals Used for Food

In Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type by Doreen Cronin, Farmer Brown’s cows use an old typewriter to compose a message requesting electric blankets to keep them warm at night. He refuses, so the cows stop producing milk. The hens also ask for blankets, and when they’re denied, they stop producing eggs. The farmer writes back to the animals, telling them that their job is to provide food.

In reality, we know that a cow’s only “job” is to provide nourishing milk to her calf and a chicken’s only job is to protect her young from danger. Animals are not ours to use for food or anything else.

Explain to students that even though real animals can’t type, there are other ways to tell how they’re feeling. Discuss the basic needs of all animals, and ask, “Why doesn’t Farmer Brown give the cows and chickens what they want?” and “What would you do if you were a cow or chicken on Farmer Brown’s farm?” To help end animal suffering, encourage students to eat vegan foods instead of meat, eggs, and dairy “products.” To supplement this text, read TeachKind’s comic books A Cow’s Life and A Chicken’s Life.

Other books with poor messaging about animals used for food include Albuquerque Turkey by B.G. Ford and Hens for Friends by Sandy De Lisle, which both promote eating eggs.

There are a number of humane children’s books that get it right when it comes to animal rights. Read them with your students to drive home the message that animals are not ours to experiment on, eat, wear, use for entertainment, or abuse in any other way.

Need more tips on incorporating humane education into your curriculum? Sign up for TeachKind News.

By submitting this form, you’re acknowledging that you have read and agree to our privacy policy and agree to receive e-mails from us.