Teacher Spotlight: Megan Snyder

The Teacher Spotlight highlights the work of various humane educators, giving them a chance to share their stories and tips and inspire other compassionate teachers like you to take action for animals through education.

Tell us what you do at PETA as a TeachKind coordinator. What does a typical workday look like for you?

Every day is different! Some days, I’m in the office creating lesson plans and activities for the TeachKind website, answering e-mails from teachers, or chatting with them on one of our social media platforms. Other days, I’m in a local school or at a community event talking to people about the importance of teaching our children compassion for animals. A few times a year, I get to travel to various locations all over the country to table at education conferences, which is always really inspiring, because teachers and administrators come to these gatherings with open minds and are actively seeking out new and innovative ways to teach their students. It can be difficult to convince educators of the necessity for humane education when they’re busy running a classroom or a school, but when they go to a conference, it’s like they’re a student again—their sole purpose is to learn. So much of outreach and activism is trying to get people to see things from your point of view, and fortunately, every teacher I’ve met agrees that kindness should be a top priority in the classroom. They just need us to explain how to teach kids to be kind to animals—very seldom do they need us to explain why.

What’s your favorite part of your work?

I often say that there’s never a dull moment in TeachKind. We’re always growing and working on something new. For example, right now, we’re preparing to go into local schools and teach culinary arts students how to cook delicious vegan food. This is a project that our team members on the West Coast started during the last school year, and we’re excited to be bringing cooking demonstrations to the East Coast this year. I love that my job involves hands-on, interactive work like this, and I can’t wait to see students’ faces when they try their own vegan creations for the first time!

What’s your greatest challenge in your work?

TeachKind regularly receives reports of kids hurting animals. In an effort to provide people with information about the epidemic of youth violence against animals, when we get a report, we contact the school district where the child who committed the act of cruelty attends school and we offer its principals or superintendents our free resources. Finding out about these cases of cruelty to animals is always difficult, but I find comfort in knowing that through my work, I can at least plant seeds in the minds of thousands of teachers and administrators. Many of them take us up on our offer of information, and we’re thrilled to help guide them in their efforts to teach kindness. Some may not implement humane education in their school immediately, but at least now they know that cruelty to animals is a widespread problem that we should all be alarmed about and that teaching students to have empathy for others is the solution.

Talk to us about your humane education journey. Who or what inspired you to start teaching compassion for animals?

I went vegetarian as a teenager and then vegan when I was in college. I started teaching shortly after that but never thought to incorporate animal rights into my lessons. As is the case with so many teachers, it just never occurred to me. Still, my compassion for animals seeped into my teaching. When helping eighth graders peer-edit their essays, for example, I’d point out that using the impersonal pronoun “it” to refer to animals suggests that they’re nothing more than inanimate objects—equal to a desk or a chair. When I’d explain it this way, not only did my students seem to suddenly understand that animals are living, feeling beings, they’d also remember what a pronoun is and its function in our language. That’s the wonderful thing about bringing animal issues into classroom conversation—the lesson in empathy doesn’t have to be separate from the lesson in reading or writing. The two points of focus can actually support each other.

Some teachers struggle to understand how to incorporate animal issues into their curriculum. What are some specific ways you did this?

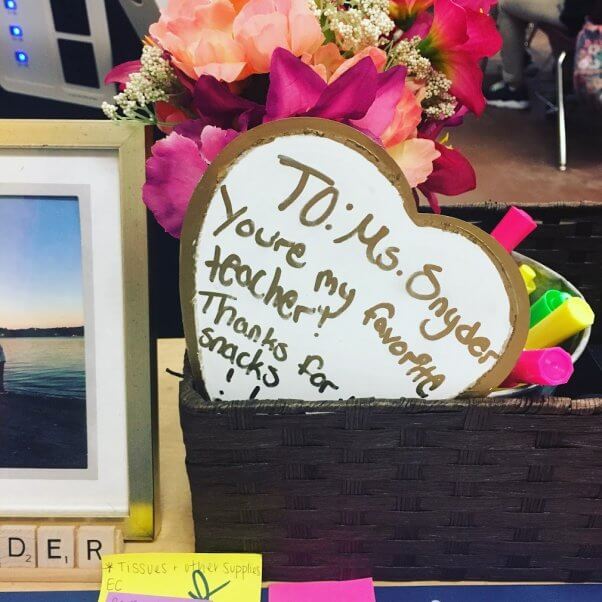

It can be as simple as keeping vegan snacks on hand. I used to have students who didn’t have a lot of food at home and needed something to keep them full during the school day. I always kept my classroom stocked with vegan granola bars, popcorn, and candy as well as fruit. On special occasions, like the day before the winter holiday break, I’d treat my students to vegan doughnuts, and they were always blown away by how tasty they were. During finals week, I’d let students use my classroom coffee machine to make hot cocoa, and I always provided soy milk. I also made a point to talk about animals as individuals. On the first day of school, like most teachers, I used to tell my students a little bit about myself and my family, and I was always sure to include my animal companions in this conversation. Just talking about animals as the individuals they are signals to students that that’s normal and appropriate. For many, that might be the first time they hear someone speak about an animal’s thoughts and feelings, and it can be very effective.

How did learning compassion for animals benefit your students? Do you have any particularly inspiring “transformation stories”?

Once, a student told me that her family could no longer care for their dog, so they abandoned her at a local park. She later told me that the dog had been found and taken to a shelter, which her family was relieved to hear. At first, I was taken aback by how matter-of-factly she told me this story—she didn’t seem at all sad or ashamed. Then I realized that treating animals like objects was seen as normal in her family. She wasn’t cruel or heartless, and I assume that the rest of her family wasn’t, either—they just didn’t know any better. I keep that student and her family in mind when working with teachers today. I try not to judge them for viewing animals in the way they do.

How would you handle inhumane school field trips?

Early on in my teaching career, I found myself substituting for a teacher on a field trip to a farm with a petting zoo. I was anxious, because I didn’t take my daughter to facilities that allow people to touch animals but my principal was counting on me to chaperone a small group of students with special needs on this outing. I’d resolved to keep an extra-close eye on my group and try to redirect them to some other aspect of the farm. When we arrived, the adults on the trip were told that we’d be rotating with our groups between three activities: going on a hay ride around the property, picking pumpkins and painting them, and going for a guided nature walk on which we’d learn about native wildlife and how to tell the age of a tree. It turned out that multiple parents had raised concerns about their kids touching the animals, and I’m sure most of the teachers didn’t want to have to monitor students around the animals, either. So it was decided that we’d just avoid that part of the farm altogether. The students and all the teachers and chaperones had a blast doing all the activities on our schedule, and none of the animals had to be stressed out or put in harm’s way because we were there. I remember thinking on the bus ride back to school that all it took was for a few kind people to speak up—and that field trip went from something potentially dreadful to a truly memorable experience.

What challenges—if any—did you face in the classroom, and how would humane education help overcome them?

One of the greatest challenges I faced in the classroom was motivating my students to learn. I was constantly trying to think of ways to make reading and writing relevant to them—I wish I’d known that the answer was wagging his tail right in front of me! I have a very close bond with my dog, Owen, and many of my students shared that same type of bond with their animal companions. Where we lived, people often let their cats outdoors unattended and kept their dogs chained. I just know that if I’d tasked my students with researching and writing about solutions to these problems, they could have written pages about their thoughts on them.

What advice would you give someone who wants to start teaching humane education but isn’t sure where to begin?

Pick an animal issue that’s relevant to your students. If you live near SeaWorld, have them watch Blackfish and then host a class debate on whether or not it’s ethical to imprison animals for entertainment. If they’re concerned about the environment, have them research the relationship between animal agriculture and the climate crisis. Or start small: One easy thing we can all do to model kindness for our students is to stop squishing bugs. With a little creativity, lessons on kindness to animals can be incorporated into any subject area at any grade level.

Where do you see your work taking you in the next five to 10 years?

TeachKind has grown so much in the last year that it’s hard to imagine where we’ll be in another five—let alone 10! I hope to mobilize our local teachers by offering regular training sessions here at the Sam Simon Center, PETA’s headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia. I hope that humane education someday becomes as ubiquitous as special education and character education. No one questions that the latter are necessary and beneficial to students. It’s just a matter of time until people realize that the former also needs to be integrated into every single curriculum.

What did you learn from your students?

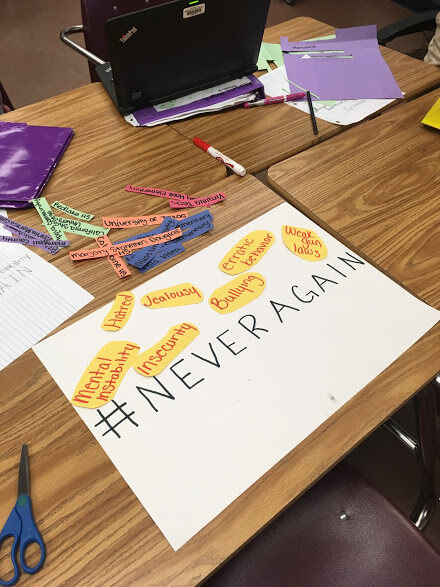

My students demanded authentic learning experiences. They often asked me why they needed to learn how to write essays and letters or when knowing how to determine an author’s purpose for writing would ever benefit them in the real world. After one of my students threatened to shoot up our school in the wake of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School attack, we were all feeling really despondent and aimless. I had my students journal about their feelings—no holds barred—and many of them expressed that they wanted to do some kind of class project on the issue of gun violence in schools. Mind you, these were eighth graders who struggled to read at grade level, were chronically truant, or otherwise faced serious roadblocks to learning. I was absolutely stunned when one group took it upon themselves to interview one another about their thoughts on gun violence and present a video of the interviews to the class. Another group created posters using the hashtag #NeverAgain to hang around the school and educate others about the causes of gun violence. These kids taught me that while my administrators were pressuring me to “teach to the test,” I had to get creative if I wanted to engage my students.

Knowing what I know now about humane education and its potential to motivate students academically and improve their interactions with their peers, if I ever went back to teaching in the classroom, I’d frame my entire curriculum around animal issues. These issues are all around us and closely intertwined with our day-to-day lives—you can’t drive to school or work without encountering some kind of wildlife, we share our homes with animal companions (or uninvited guests), and every day, humans exploit billions of animals for personal gain even though humane alternatives are readily available. No lesson is more applicable to life in the real world than the lesson that animals are not ours to use. I had some students with a less-than-ideal home life, and I know humane education would have really benefited and empowered them.