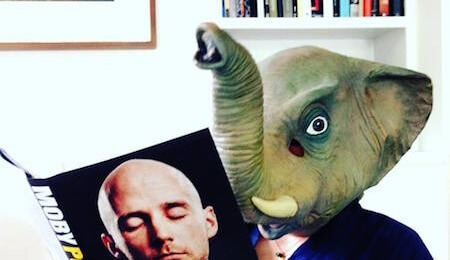

In an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle, PETA supporter Moby touches on the similarities between working on his music and writing his new book, Porcelain: A Memoir (Penguin Press, $28).

“I’m not thinking too much about the technical aspects; I’m thinking about how the music is resonating with me emotionally,” he says. “In writing this book, I felt similarly. I wanted it to be well written, ideally, and to be interesting, but ultimately I wanted there to be an emotional core that I responded to.”

Porcelain—the title is taken from a track on his 1999 mega-hit album Play—meets these criteria and more. Like the author, it’s articulate, frank, honest, and funny.

That’s no surprise to his fans at PETA. A vegan for nearly 30 years, Moby has sung the praises of going vegan, called out former Vice President Al Gore for failing to mention in An Inconvenient Truth that raising animals for food is the leading cause of climate change, opened a vegan bistro in Los Angeles called little pine, and mingled at our 35th anniversary gala.

It’s no surprise, either, that he writes with such passion, especially about animal rights. He recalls the “perfect night” when he DJed a gig on the roof of a popular New York club. Afterward, pushing his records on his skateboard through the meatpacking district, he watched and said a prayer as the sides of beef and lamb were unloaded. Then his skateboard slid through a puddle of blood.

“How could I be witnessing this horror—all of these dead animal bodies being thrown around—while the morning sun was on my face and when I’d just had a perfect night playing records?” he writes. “As I pushed my skateboard through another puddle of offal, I silently vowed, Trying to end animal suffering will be my life’s work, no matter what.”

Pivotal passages like this are balanced with lighter recollections, such as when Moby, much to his family’s dismay, celebrated his three-year vegan anniversary by fasting—over Thanksgiving. “When I became a vegan in 1987,” he writes, “in one fell swoop I extended my life expectancy and annoyed most of the people in my life.”

Porcelain also paints a vivid portrait of New York at the time. The city was dangerous and grimy, but for a poor white Christian teetotaler from Connecticut who was paying a $50 squatter’s fee to live in an abandoned warehouse without heat or running water, “the filthy epicenter of the most remarkable city on the planet” was heaven.

The stories he tells—including about spinning records at a sex party in midtown Manhattan, playing for thousands at a rave in the British countryside, and encountering Miles Davis, Madonna, and Big Daddy Kane—capture an authentic sense of time and place. Remarkably, Moby didn’t keep any journals. “For some reason,” he told the Chronicle, “I just remember everything.”

Readers will be glad he did.

Text VEG to 73822 to get the latest vegan lifestyle tips, recipes, and urgent action alerts texted right to your phone.

Terms for automated texts/calls from PETA: https://peta.vg/txt. Text STOP to end, HELP for more info. Msg/data rates may apply. U.S. only.