The following article was written by Paula Moore.

A Siamese cat wails in grief for her dead sister, who had been her constant companion for 14 years. Horses form a circle around the newly dug grave of their equine friend and stand in silent vigil. Following the sudden death of his mother, a juvenile chimpanzee named Flint loses the will to live (Jane Goodall hauntingly describes Flint as “hollow-eyed, gaunt and utterly depressed”) and dies himself three weeks later. A grieving dolphin mother desperately tries to revive her dead calf by repeatedly lifting the small body above the surface of the water and pushing it under again. Tarra, an elephant at The Elephant Sanctuary, gently carries the lifeless body of her friend, a little dog named Bella, who was likely killed by coyotes, to a barn where caretakers will find her and later visits Bella’s grave.

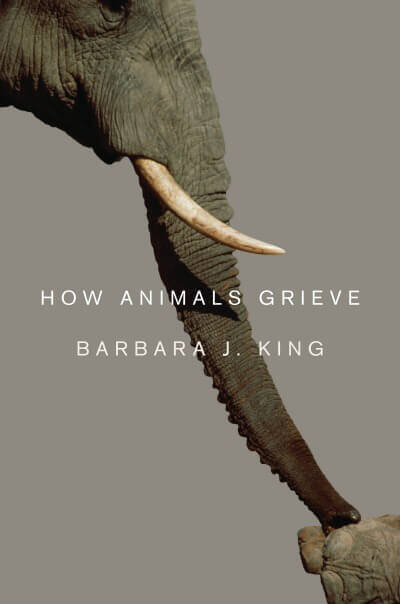

Through science as well as numerous stories such as the ones above, Barbara J. King—a professor of anthropology at the College of William and Mary and a commentator on NPR’s science blog, 13.7—makes a compelling case for the rich and deep emotional lives of other animals in her new book, How Animals Grieve.

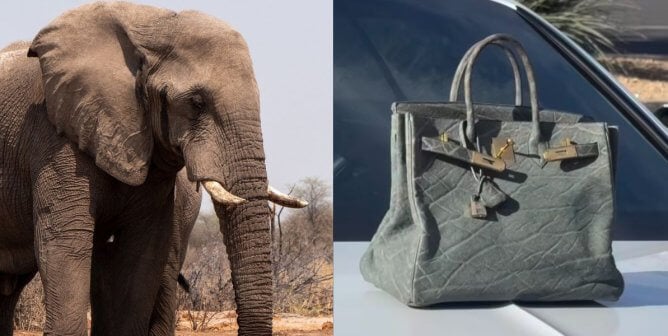

As animal people, we’ve all heard stories of elephants carefully caressing the bones of their dead loves ones or of mother apes carrying the bodies of dead infants (sometimes long after the corpses have begun to rot). Elephants and apes are fiercely intelligent, and that they grieve does not surprise us. But King reminds readers that “grief is linked not to some feat of thinking but instead to feeling.” In other words, intelligence (at least how we humans tend to quantify it) is not an accurate measure of emotion. We do not need to master the concept of death—or even dread it, as humans so often do—in order to form strong bonds with others and mourn their loss.

What, for example, are we to make of the story of the sea turtle Honey Girl, who was cruelly killed by human hands and memorialized by local residents? Among the visitors to the memorial—which included a large photograph of Honey Girl—was a single male sea turtle, who settled in the sand in front of the photo and sat staring at it for hours. Was the male turtle mourning his mate? As a scientist, King is not prepared to make a case based on one anecdote, but she does posit that perhaps scientists have never “discovered” turtle grief because they’ve never bothered to look for it. “[T]he old bugaboo of anthropomorphism still prevents some scientists from even trying to collect the needed data,” she says. There’s also this: “To plumb the depths of animal thinking and feeling means to reassess how we, collectively as a society and individually as persons, treat other animals.” For some people, then, it may simply be easier to go on pretending that animals do not think and feel.

Many of the stories in How Animals Grieve are heartbreaking (yes, you will cry). But with the sadness also comes joy since love and loss are two sides of the same coin. As we consider the richness of other animals’ emotional lives, we should keep in mind the theme of King’s book: “Where there is grief, there was love.”

PETA is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Text VEG to 73822 to get the latest vegan lifestyle tips, recipes, and urgent action alerts texted right to your phone.

Terms for automated texts/calls from PETA: https://peta.vg/txt. Text STOP to end, HELP for more info. Msg/data rates may apply. U.S. only.