The Silver Spring Monkeys: The Case That Launched PETA

In the summer of 1981, PETA’s founder, Ingrid Newkirk, leafed through the pages of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s list of laboratories, picked the closest one, and asked her colleague, Alex, to see if he could get inside. He did and began working as a volunteer at the Institute for Behavioral Research (IBR). IBR was a federally funded laboratory in Silver Spring, Maryland, now closed down for reasons that will soon become apparent.

What PETA Found Inside the Laboratory in Silver Spring

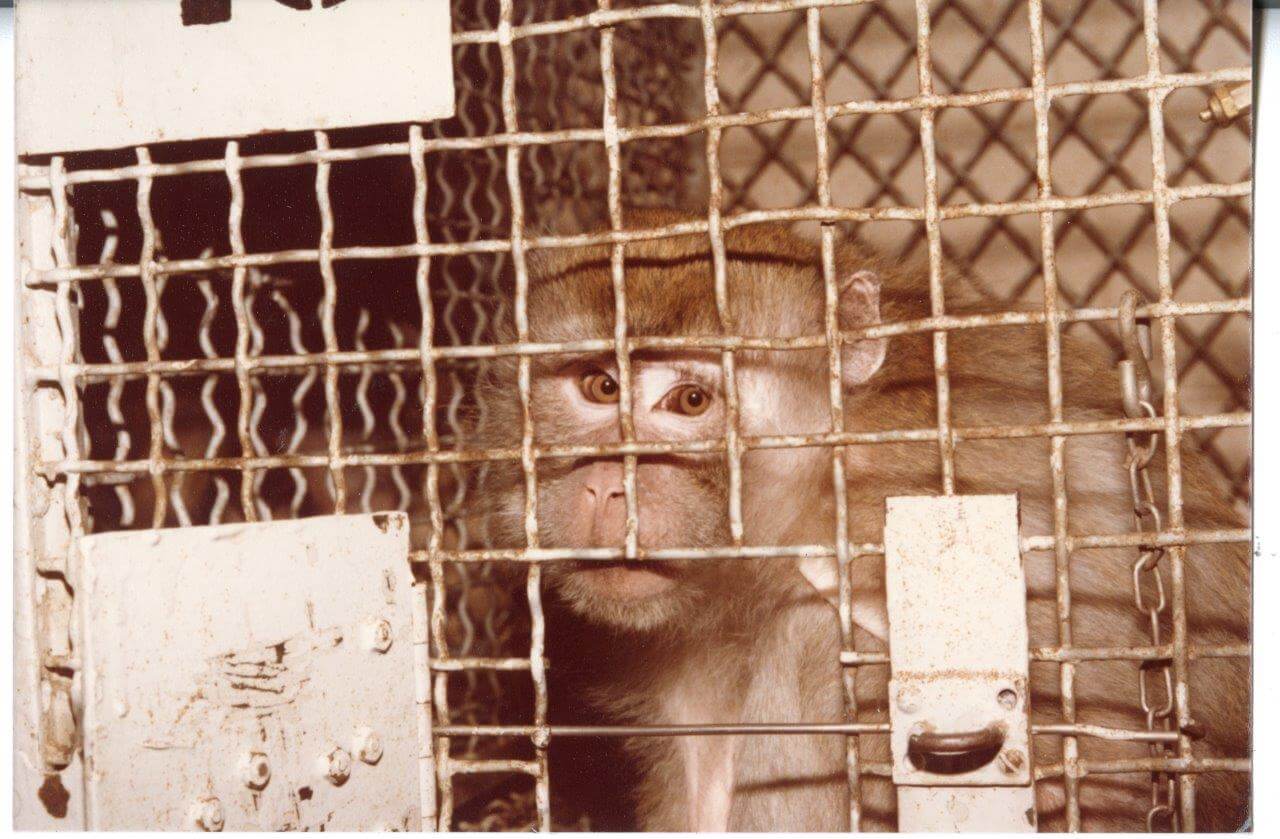

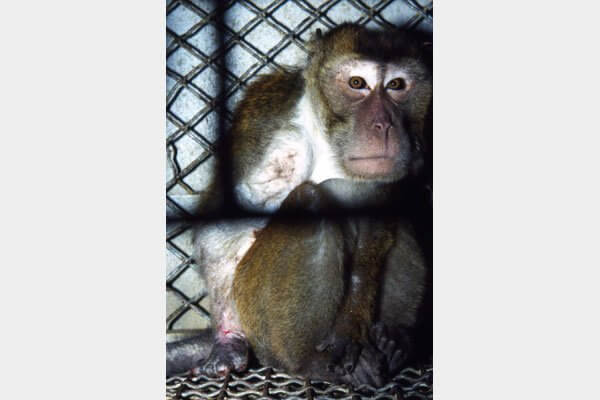

It was run out of a warehouse by psychologist and animal experimenter Edward Taub, a man with no medical training. There, we found 17 monkeys living in tiny rusty wire cages caked with years of accumulated feces in a dungeon-like room. There was no veterinarian to tend to their serious wounds, and they had a lot of them.

WATCH:

Taub’s Experiments on the Silver Spring Monkeys

Taub, who also had no veterinary training, nevertheless subjected the monkeys to surgeries in which he severed their spinal nerves, rendering one or more of their limbs useless. By means of electric shock, food deprivation, and other cruel methods, he forced them to try to regain the use of their impaired limbs to pick up raisins from a tray—or else go without food.

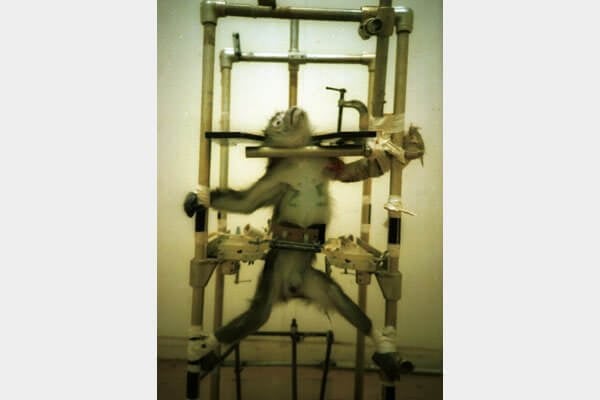

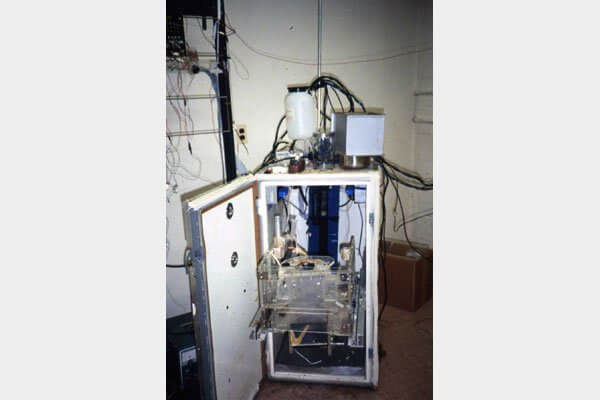

In one experiment, monkeys were shut inside a converted refrigerator and repeatedly electro-shocked until they finally used their disabled arm, if they could. The inside of the refrigerator was covered with blood. In another experiment, monkeys were strapped into a crude restraint chair—their waist, ankles, wrists, and neck held in place with packing tape—and pliers were latched as tightly as possible onto their skin, including on their testicles.

The trauma of the monkeys’ imprisonment and treatment was so severe that many of them had ripped at their own flesh, and they had lost many of their fingers from catching them in the rusted, jagged cage bars.

Workers often neglected to feed the monkeys, and the animals would desperately pick through the stinking urine and fecal waste in trays beneath their cages to find something to eat.

PETA gathered meticulous log notes detailing what was happening inside IBR and secretly photographed the crippled monkeys and their horrendous living conditions. Then, after lining up expert witnesses and showing them around the laboratory at night, PETA took the evidence to the police—and an intense, decade-long battle for custody of the monkeys ensued.

This groundbreaking investigation led to the nation’s first arrest and criminal conviction of an animal experimenter for cruelty to animals, the first confiscation of abused animals from a laboratory, and the first U.S. Supreme Court victory for animals used in experiments. It even led to landmark additions to the Animal Welfare Act—and unrelenting public scrutiny of the abuse that animals endure in experimentation. And IBR closed its doors.

PETA has scored many victories for animals in laboratories since the landmark Silver Spring monkeys case, but tragically, experiments like this still go on. You can help by asking your congressional representatives to divert public money from cruel animal experiments into promising, lifesaving, and relevant clinical and non-animal research.