Animal Experiments at George Mason University

PETA is pulling back the curtain on taxpayer-funded animal experiments at George Mason University (GMU) to reveal violations.

- Official Animal Welfare Concerns at GMU

- Number of Animals Used

- Media Coverage

- Examples of Animal Experiments

- Public Funding

Official Animal Welfare Concerns at GMU

GMU, which includes the Krasnow Institute for Advanced Study, has used an untold number of animals—including elephant shrews, mice, and rats—in experiments.

Unlike most publicly funded animal testing facilities in Virginia, GMU doesn’t have a statement posted on its website regarding a commitment to the principles of the “3Rs”: Replacement of animal-based models with innovative technology, Reduction in the number of animals used in experiments, and Refinement of scientific methods to minimize pain and suffering.

Oversight agencies responsible for ensuring compliance with federal animal welfare standards have documented the following issues at GMU.

- During a transcardial perfusion—in which an animal’s circulatory system is flushed with saline or a fixing agent through a needle inserted into the heart while the animal is deeply anesthetized but still alive—a mouse “exhibited signs of waking up,” then was “immediately re-anesthetized with isoflurane prior to continuing the perfusion and subsequent euthanasia procedures.” It was also determined that the procedure was performed in an area “not approved for animal use for this protocol.”

April 27, 2023, self-reported NIH OLAW report (F)

- Expired pain-relieving drugs and antibiotics were administered to rats during 13 survival surgeries and recoveries over the course of four months. The drugs had expired two years before the time period covered by the violation. Although the attending veterinarian “did not believe the animals to be in pain or distress that required further veterinary action,” the university noted that “the severity in which these incidents of improper oversight of care and use to our most vulnerable animals who undergo survival surgery procedures is a serious deviation from Mason policies and Assurance” as well as Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (PHS Policy) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

February 22, 2023, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Animal Plant and Health Inspection Service (APHIS) Inspection Report: One violation

- A responsible adult wasn’t present to accompany APHIS officials during the inspection process at the Krasnow Institute.

February 22, 2023, USDA APHIS Inspection Report: One violation

- A responsible adult wasn’t present to accompany APHIS officials during the inspection process at GMU.

July 7, 2022, self-reported NIH OLAW report (D)

- A “technician was practicing tail vein injections on a mouse under chemical restraint and used saline for the injection instead of a contrast agent approved to use” in the applicable Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol. Although the mouse died before recovering from anesthesia, the university’s institutional official stated that the animal’s death “was determined to be an unfortunate event and not directly caused by the noncompliance.”

Number of Animals Used at GMU

GMU submits an approximate number of all animals used in experiments to the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International annually in order to maintain accreditation. This number includes commonly used species not covered by the federal Animal Welfare Act (AWA), such as amphibians, reptiles, fish, invertebrates (including crustaceans and insects), birds, rats of the genus Rattus, and mice of the genus Mus, who are “bred for use in research.” According to the AAALAC annual report for 2022, species not covered by the AWA—mice, rats, birds, and cold-blooded species—accounted for 100% of the animals used at GMU.

| Type of Animal | Number Used |

| Fish | 50 |

| Mice | 1,600 |

| Rats | 30 |

| Reptiles | 60 |

| Total | 1,740 |

Examples of Experiments Involving Animals at GMU

The following experiments were recently conducted at GMU, and many of them were publicly funded:

Optimization of tissue sampling for Borrelia burgdorferi in white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus)

A total of 90 wild white-footed mice were lured into baited traps and killed by carbon dioxide asphyxiation or “vertebral dislocation upon triggering the trap mechanism” so that their tissues could be analyzed.

Wheel-running behavior is negatively impacted by zinc administration in a novel dual transgenic mouse model of AD

Mice who were injected with human gene mutations so that they would develop Alzheimer’s disease were subjected to “a battery of behavioral tests” before being used in the experiment. These tests included mazes intended to cause anxiety and the forced swim test, in which an animal is confined to an inescapable container of water to measure how long he or she fights to keep their face above water. During the experiment, mice were given zinc-supplemented drinking water and “tested for daily wheel running activity.”

Immune-modulating activity of hydrogel microparticles contributes to the host defense in a murine model of cutaneous anthrax

Experimenters injected the hind footpads of female mice with anthrax-causing bacteria and also injected some of them with engineered microparticles designed to help clear the infection. Inflammation of their footpads was then observed for two weeks or until they died from the infection, whichever came first.

Spatial learning is impaired in male pubertal rats following neonatal daily but not randomly spaced maternal deprivation

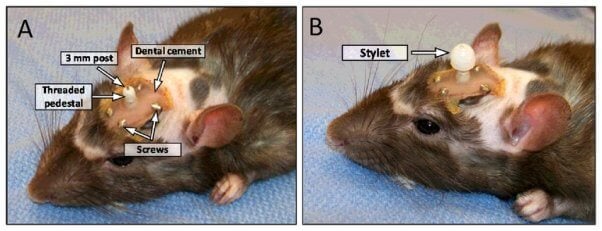

Experimenters subjected baby male Long-Evans (aka “hooded”) rats to maternal separation by isolating them for three hours daily for 10 consecutive days starting when they were 1 or 10 days old. The rats then underwent surgery in which their skulls were opened and a drug-delivery tube was permanently implanted in their brains. At 40 days old, the rats were placed multiple times into a water maze, where they were forced to swim in a pool of water mixed with white paint until they found a hidden platform, and then they were killed. Virginia Tech (VT) was also involved in this experiment. (To learn more about animals used in experiments at VT, click here.)

Media Reports Concerning Animal Testing at GMU

- April 29, 2019: “Some George Mason University students want to end animal experiments on campus,” DC News Now

Public Funding for Experiments on Animals at GMU

In 2023, the Commonwealth of Virginia and its localities gave public universities more than $166 million for animal and non-animal research. Currently, no information is available indicating how much money is spent on animal experimentation in Virginia. The table below shows the total annual research funds received by GMU for the past nine years, including public funding.

In 2024, GMU spent $5,775 of its funding on AAALAC “accreditation” fees.

| Year | State/Local Govt. | Federal Govt. | All Sources |

| 2014 | $1,945,000 | $61,877,000 | $98,680,000 |

| 2015 | $1,711,000 | $63,600,000 | $106,410,000 |

| 2016 | $3,041,000 | $58,864,000 | $108,899,000 |

| 2017 | $3,289,000 | $57,345,000 | $112,404,000 |

| 2018 | $3,156,000 | $69,481,000 | $149,138,000 |

| 2019 | $3,370,000 | $96,307,000 | $186,267,000 |

| 2020 | $3,750,000 | $104,070,000 | $221,006,000 |

| 2021 | $3,387,000 | $103,712,000 | $214,207,000 |

| 2022 | $5,816,000 | $119,406,000 | $230,068,000 |

| 2023 | $4,311,000 | $125,437,000 | $252,239,000 |

Source: Higher Education Research and Development Survey, Table 83 for FY 2014, Table 82 for FY 2015, and Table 5 for FY 2016–2023