The Fashion Train as a Vehicle for Activism:

An Interview With Leanne Mai-ly Hilgart

Leanne Mai-ly Hilgart is consistently recognized for her beautiful and innovative contributions to the cruelty-free fashion scene, but if you haven’t yet heard about her all-vegan brand, VauteCouture, through media such as Business Insider, CNN, Teen Vogue, and Oprah.com, check out this introduction to her business, which will ensure that you’re in the know. With countless roles under her belt (she’s a model-turned-business student-turned-designer-turned-force of nature) and a drive that matches her résumé, we had to know where Leanne finds her daily inspiration to be a hero for animals. One thing’s for sure—after reading her story, all self-imposed inhibitions will be out the window, and like us, you’ll be busy brainstorming to find a way to improve the world alongside her.

When and how did you first become aware of animal rights issues?

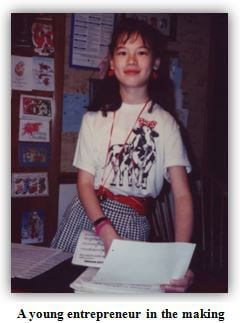

When I was 6, a girl down the street got a rabbit fur coat for Christmas. I didn’t know anything about anal electrocution or fur farms, but I knew that some rabbits had lost their lives so that this silly coat could exist. When you’re little, sometimes things are simple like that. At 8, I coordinated my friends and got them to go door to door to sell art we had made in order to raise money for the local animal shelter. I’m pretty sure that we spent more on materials than we raised, but my sweet, sweet parents let me donate it all. (Thanks, Mom and Dad!)

When I was a kid, my mom loved donating to all different organizations for human rights, the environment, and animals, which resulted in an epic sticker collection for me. She’d give me the free gifts that came with the memberships, including PETA’s stickers: “Unseen they suffer, unheard they cry, in agony they linger, in loneliness they die.” I stared at these stickers in my sticker book and said to myself, “I need to know: What are we doing to them?” So I wrote my report based on research from the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine and the National Anti-Vivisection Society as well as books such as John Robbins’ Diet for a New America and Peter Singer’s classic Animal Liberation and titled it “Being Cruel Isn’t Cool,” which I then sold to a T-shirt company as my first nationally

sold slogan T-shirt, for which I was paid in T-shirts! When I visited my uncle’s dairy farm a few months later, I was playing with cows all day before coming in for dinner—steak dinner. I tried, as a 10-year-old, to be polite and eat at least a bite, but as uncomfortable as it was to decline that night’s dinner, it was more uncomfortable to betray the cows, my friends, on such a basic level. My body refused to swallow, and I have never eaten an animal again.

What inspired you to start VauteCouture?

As a 6-year-old, I loved creating art, talking to strangers, and sticking up for animals. I’ve started to think that who you are at 6 is a great role model for who you can be as an adult. It took me 20 years to realize this, starting with when I gave up my college major at 21 and continuing through the next five years of searching and searching for that thing that I was supposed to do. In college, I was an education major. I wanted to become an elementary school principal. As much as I loved school as a kid, learning from the most inspiring teachers (Hi, Ms. Kinder and Mr. Larson!), I realized later that many school systems were structured to turn children into exchangeable parts of society instead of proactive participants in it, empowered to make the world a better place. The latter was what I wanted to do, more than anything. I was forced to ask myself, “What am I meant to do, if not this thing that I’ve spent the last four years dedicated to?” And that became the question: “What is it that I do most effortlessly?” I realized that the easiest thing for me is spreading awareness about issues that I care about, in a welcoming way. Next I wondered, “What is that in the real world?” It was marketing.

Through research and internships, I began to see the potential for entrepreneurship to be an effective vehicle for activism. I realized that as an individual, I can do something once, but as a business, each part of the process is done an exponential number of times, which gives it the power to do a great deal of good or harm through each step of the process. The difference depends on the entrepreneur’s end goal. As a kid, I always thought that people who ran slaughterhouses and fur farms must hate animals, but it was through learning about business that I realized that cruelty to animals in the fashion and food industries and many others is a result of a flawed system in which we turn everything and everyone into machines. The industrialization of production is a system that was built to minimize costs and maximize profits. And if you think about it carefully, this means that a living being’s well-being is just considered an added cost. This is why I decided that I needed to start a business dedicated to animals, one that would innovate in such a way as to declare: “We don’t need to use animals in this industry again.”

Around this time, I took a modeling contract in Hong Kong, where the Eurasian food, a million things to do, the tiniest apartment ever, and Po Lin Monastery, which you can reach by a cable car up in the clouds, made for a magical few months. Without my studies, though, I ended up bored each night after castings and shoots, needing an opportunity to create and for my brain to play. I was reading Rules for Revolutionaries by Guy Kawasaki, How to Be Lovely (a collection of Audrey Hepburn interviews), and Unleashing the Ideavirus by Seth Godin at the time, and as I ran through all the business ideas that I had never really given a chance before, I hit upon one that answered a question that I had been confronting each winter: “How can I wear a coat in Chicago that looks like me, is warm enough for a Chicago winter, and is cruelty-free?” It didn’t exist.

I almost didn’t start Vaute because I didn’t know if there was a market for vegan coats. There had been many wonderful accessory labels that were leather- and fur-free but none that innovated in apparel, cold weather apparel in particular. People, including even many vegans I knew, still thought they needed to wear animals in order to be warm in the winter. It was then that it hit me: If I could create a winter dress coat that was warmer than a wool coat, it would be my contribution to saying that we never need to wear animals again, and this would be something that women who weren’t vegan would want to wear, too. It was through this building process to create change that I was able to show women that what they wear makes a difference, which only made me want to share all the other ways in which they could empower themselves to create change throughout their daily choices. This would be my activism. This would be where my life’s happenstance and lessons could come together. Modeling taught me how a casting and a photo shoot operated, teaching taught me how to present ideas and how people learned best, and activism taught me how to start difficult conversations. My childhood love for creating art would be honored (and I’m so very grateful for that), even though I had pushed this far down into my heart and not listened to it for so many years.

Did it sound crazy to start a vegan fashion label, when most people thought vegan was only a way of eating? It didn’t matter. I couldn’t sleep if I didn’t do it. And for all the business plan competitions that I entered, only to find that no one understood my ideas, I was fine with that. Sometimes when you travel, you find freedom from constrictions that a fresh city can show you were never really there in the first

place. I realized on those Hong Kong nights, far away from my routine and daily chatter, that I had never asked for permission or approval for anything great that I had ever done in my life. I had just done them. I had just done them because I absolutely had to. I had no say in this myself. I just felt the momentum was there, the way that you know it when you’ve found the love of your life or the way I felt when I visited Brooklyn—when something is so right that you can’t say no. You don’t need to tell anyone or ask what they think because it’s just there for you—it’s yours. This is how I felt when I came upon the idea of Vaute. And so, in the fall of 2008, I quit my contract with Ford Models and my full-ride MBA at DePaul and started 80-hour workweeks with my life savings to develop what would become the first line of VauteCouture winter dress coats.

Your coats are known for the warmth that they provide in extreme cold, without using any wool or down. How were you able to pull this off, and can you tell our viewers what happens to animals in the wool and down industries?

During my initial eight months of fabric research, while I was trying to hit many different solution points—warmer than wool, wind-proof, snow-proof, the right drape and feel of a dress coat, slimming, mainstream pricing, eco-consciousness—I realized that the typical eco-conscious plant-based organics weren’t going to cut it in terms of warmth or protection. So I turned to high-tech mills at the cutting edge of sustainability and worked with them to create new ways of using high-tech eco-conscious fabrics (made from a blend of organics, recyclable materials, and recycled fibers). The end result was the creation of something that people from cold cities, who don’t yet know about how awfully animals in fashion are treated and killed, could also love because they’re created with the warmth and protection of a coat from Patagonia but the look and feel of a dress coat. Before starting Vaute, I realized that creating an alternative has a limited market and impact. Creating something better? That has the chance to influence an entire industry, to show the possibilities when we look at things differently. For me, taking animals out of the equation was a chance to look with fresh eyes at how a winter dress coat is constructed in a way that it had never been looked at before, because the traditional fabrics were “good enough” for the general public. Because I had another reason—animal rights—to look again at something that had gone on being “good enough,” I was given this opportunity to reimagine what a winter dress coat could be. I realized that not using animal fibers had become the opportunity to look in a new way.

As for wool and down, the first thing I want to say is that these industries are not made because people are cruel. The people in these industries are also exploited and treated like cogs. The entire system is flawed because it objectifies everything and everyone in it to become only regarded for their cost and output, which means that most animals raised for fashion are raised on factory farms, and the practices per fabric are created just to produce the most fiber. You can get the most down out of birds by hanging them upside down and plucking their feathers out while they’re still alive, because then they will grow them back, and you can do it again in a few months. Of course, this does not take into account the sheer pain of being plucked alive repeatedly over your short lifetime. It goes on for a few years until this sweet tortured bird is considered no longer as productive and, in the end, is killed anyway. For wool, a sheep is sheared for efficient speed, often lopping off parts of skin, and because the industry wants to create the most wool for the least amount of input, sheep

As for wool and down, the first thing I want to say is that these industries are not made because people are cruel. The people in these industries are also exploited and treated like cogs. The entire system is flawed because it objectifies everything and everyone in it to become only regarded for their cost and output, which means that most animals raised for fashion are raised on factory farms, and the practices per fabric are created just to produce the most fiber. You can get the most down out of birds by hanging them upside down and plucking their feathers out while they’re still alive, because then they will grow them back, and you can do it again in a few months. Of course, this does not take into account the sheer pain of being plucked alive repeatedly over your short lifetime. It goes on for a few years until this sweet tortured bird is considered no longer as productive and, in the end, is killed anyway. For wool, a sheep is sheared for efficient speed, often lopping off parts of skin, and because the industry wants to create the most wool for the least amount of input, sheep  are bred to have wrinkly skin so that they bear more wool per animal. Unfortunately, there are bugs that like to live in those wrinkles, and these animals often have skin cut off their nether regions (a process known as mulesing) to keep bugs from laying eggs in there. After being considered no longer productive, they’re shipped off to the Middle East, literally on top of one another and dying in transit with no food and water, only to be killed for halal meat. From one cruel production process to the next, sheep, my very favorite animals in the whole world (visit Farm Sanctuary or Woodstock Farm Animal Sanctuary, and you’ll see why!), are treated as machine parts and used up in sad, painful ways, until they die. People often think that wool is just the result of a haircut and that these animals live out their lives peacefully. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Animals don’t belong in the business equation, and I will do everything it takes to make sure that there’s no need for them to be in the future by giving my all to create animal-free apparel that is better.

are bred to have wrinkly skin so that they bear more wool per animal. Unfortunately, there are bugs that like to live in those wrinkles, and these animals often have skin cut off their nether regions (a process known as mulesing) to keep bugs from laying eggs in there. After being considered no longer productive, they’re shipped off to the Middle East, literally on top of one another and dying in transit with no food and water, only to be killed for halal meat. From one cruel production process to the next, sheep, my very favorite animals in the whole world (visit Farm Sanctuary or Woodstock Farm Animal Sanctuary, and you’ll see why!), are treated as machine parts and used up in sad, painful ways, until they die. People often think that wool is just the result of a haircut and that these animals live out their lives peacefully. This couldn’t be further from the truth. Animals don’t belong in the business equation, and I will do everything it takes to make sure that there’s no need for them to be in the future by giving my all to create animal-free apparel that is better.

How would you describe your style and your collection?

I’m inspired by vintage clothing and love mixing patterns and textures. One of my favorite things is borrowing clothes made for guys. In the winter, you’ll see me in this oversized accidentally vegan fisherman sweater that I found in a charity shop in London for 4 pounds. Joshua Katcher was so mad that I found it first. (Too bad: He was eating waffles at the Gallery Cafe, and I ran over to  find something good!) I also wear flannels from a thrift market in Seoul that I picked up on tour while doing a fashion show for PETA Asia and CARE. Otherwise, as a girl who loved ballet class as a kid (but still has never gained much balance or grace), I’m drawn to movement and comfort-oriented dance-inspired pieces such as bodysuits and high-waisted miniskirts with sweater tights—anything that looks and feels like I just came from dance class. I want to be able to move and eat and eat. (It’s why most of the dresses that I design have full skirts with pockets.)

find something good!) I also wear flannels from a thrift market in Seoul that I picked up on tour while doing a fashion show for PETA Asia and CARE. Otherwise, as a girl who loved ballet class as a kid (but still has never gained much balance or grace), I’m drawn to movement and comfort-oriented dance-inspired pieces such as bodysuits and high-waisted miniskirts with sweater tights—anything that looks and feels like I just came from dance class. I want to be able to move and eat and eat. (It’s why most of the dresses that I design have full skirts with pockets.)

When I design, I focus on timeless silhouettes. Audrey Hepburn is my greatest inspiration—she’s smart, kind, humble, and happy. She appreciates the adventure of life and doesn’t give herself too much credit. That is the kind of girl I like best. But I’m inspired by everything and infuse various things into the details of my designs: geometry, origami, nature, effortless New Yorkers on the subway, my friends, and my constant vintage hunting worldwide.

I think it’s time to take back our creative process when it comes to how we dress. After the factory collapse in Bangladesh, which killed more than a thousand workers just for fast fashion, it seems that people are finally asking, “How were our clothes made? Who made them?” But people assume that wearing ethical clothes is expensive. What I’ve discovered is that if I purchase mostly thrift and vintage pieces, I can curate a closet that is entirely me and that I participated in, with clothing that I won’t see again on someone else like I would if I shopped almost exclusively at the mall of fast fashion. Then, I can invest in pieces and accessories from companies that I really believe in and support business practices that I want to see more of. Now, I have pieces that mean something to me, that have a story, such as that time in Portland or the thrift market in Michigan, where the owner asked me if I was going to buy that dress for Halloween. (“No, Brooklyn.”) As far as how I design, I’m inspired by color, pattern, and things that don’t take themselves so seriously—especially when it’s winter and everyone else is wearing black and gray, and you just are waiting for some sun and smiles and Friday and summer. Be some sun—be some summer! (And I don’t just mean Zooey Deschanel, but she’s adorable, yes.) Be happy! Audrey Hepburn always said that the “happiest girls are the prettiest” and indeed, “You’re never fully dressed without a smile.” (Isn’t angst out yet? Finally?)

What’s the most common misconception about vegan style, and what are your tips for making the transition to a cruelty-free life?

Let’s see—people think vegan style is cheap, ugly, and difficult or not eco-conscious. There’s a study (I can send you the link!) that shows a real fur coat is five times more toxic for the environment than a faux-fur coat. People don’t realize that so many chemicals need to be added to make a naturally decaying thing, like skin, last forever, and they also don’t think about how unsustainable factory farming is—as the number one contributor to greenhouse gasses. As far as cheap and ugly go, I prefer buying vintage and thrift, which can be really cheap, but in a good way because then we are reusing clothing and giving it a second life. The fun part of thrift is that you are creating your wardrobe to represent how you feel and what you want to say, not dictated by fashion trends or magazines. You are your own stylist, on the hunt for the piece that is relevant now from the church clothing swap, using your eye and your taste to combine it with your investment piece from a company that you believe in (and probably from a company on this awards list).

fun part of thrift is that you are creating your wardrobe to represent how you feel and what you want to say, not dictated by fashion trends or magazines. You are your own stylist, on the hunt for the piece that is relevant now from the church clothing swap, using your eye and your taste to combine it with your investment piece from a company that you believe in (and probably from a company on this awards list).

As far as difficult goes, it’s just not! I grew up in the ‘burbs of Chicago, and if you’re good at reading labels on food, just extend that to your wardrobe. Look out for anything that calls itself something unrecognizable: Cashmere is wool, angora is rabbit fur, and faux fur is often actually real fur mislabeled, so I tend to stay away from faux fur altogether—except for the petal-pink obviously faux earmuffs that I designed. (OK, petal pink might be my weakness always!)

What do you see for the future of vegan fashion?

I’m currently working on sweaters, bags, and gowns that are vegan, eco-conscious, and made ethically for all the brides who have asked me for years and so that our celebrity clients can tell the world, “Yes, no animals were harmed in the making of this dress.” But I don’t really see it as “vegan fashion” per se. I’m giving it all to create a future in fashion: a new standard so that we can all move toward not wearing animals.

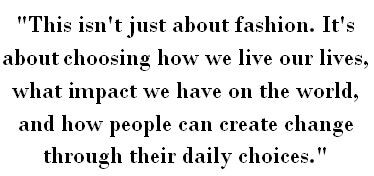

What’s next for you?

We’ve been a self-funded label for more than five years, and I’ve been feeling the momentum of our growth. We’re at a point at which I’ve done everything that I can as a self-funded company. We are ready now to open up to outside investors and grow the  leadership team. After that, I see us building communities in cities around the globe through flagship spaces and fashion trucks that collaborate with local nonprofits, rescues, and companies that care. This isn’t just about fashion. It’s about choosing how we live our lives, what impact we have on the world, and how people can create change through their daily choices. I’ve always admired Mark Constantine of LUSH, and I want us one day to be the “LUSH of fashion.” The time is right for a label that stands up for animals, the environment, and workers, and I’m trying to figure out the best way for us to do that.

leadership team. After that, I see us building communities in cities around the globe through flagship spaces and fashion trucks that collaborate with local nonprofits, rescues, and companies that care. This isn’t just about fashion. It’s about choosing how we live our lives, what impact we have on the world, and how people can create change through their daily choices. I’ve always admired Mark Constantine of LUSH, and I want us one day to be the “LUSH of fashion.” The time is right for a label that stands up for animals, the environment, and workers, and I’m trying to figure out the best way for us to do that.

For the very near next, like this week, I just busted my butt (oh, man, I need a week of naps!) to launch a subscription-based program for our animal-loving tops and statement tees, which always sell out so quickly. I figured that if I created a system in which people can pre-purchase two tops a month (and get a discount for doing so), we’d have enough cash flow to produce new designs each month, including two as benefit tees to raise awareness and funds for some favorite nonprofits (including one for PETA soon). After the tops are picked from these members first, the rest are released to the public, and that’s happening this Friday, including our “Fur Get Me Not” fox tank, T-shirt, and sweatshirt and the new versions of our “No Animals Are Harmed in the Making of This Girl” tank and “Animal Lover” tops. I hope you guys like them! You can see them all here, tell me what T-shirts you’d like us to make here, and grab a 10-pack or membership here!

For the very near next, like this week, I just busted my butt (oh, man, I need a week of naps!) to launch a subscription-based program for our animal-loving tops and statement tees, which always sell out so quickly. I figured that if I created a system in which people can pre-purchase two tops a month (and get a discount for doing so), we’d have enough cash flow to produce new designs each month, including two as benefit tees to raise awareness and funds for some favorite nonprofits (including one for PETA soon). After the tops are picked from these members first, the rest are released to the public, and that’s happening this Friday, including our “Fur Get Me Not” fox tank, T-shirt, and sweatshirt and the new versions of our “No Animals Are Harmed in the Making of This Girl” tank and “Animal Lover” tops. I hope you guys like them! You can see them all here, tell me what T-shirts you’d like us to make here, and grab a 10-pack or membership here!

Also, from now until June 15, all PETA friends get 30% off all my newest jackets and dresses using the code “LovePETA” at check-out!

Please keep in touch daily at my Instagram and our Facebook! And if you want to see my hours of quote obsessing, you can check out my Pinterest, all @VauteCouture. (New York City friends, visit our flagship store at 234 Grand St., Brooklyn, NY 11211!)

Feeling inspired? Learn more about Leanne and her line by checking out CNN’s coverage of Vaute Couture’s 2013 debut at NYFW, the first-ever all-vegan show to grace the runway!

Caution: Viewing this clip may result in an impulse shopping spree at www.VauteCouture.com and a visit to your local animal shelter!