‘PETA v. Tri-State Zoological Park’ Case Summary

Case Name: People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals, Inc. v. Tri-State Zoological Park of Western Maryland, Inc. and Robert L. Candy

Index Number: 1:17-cv-02148-MJG

Court: U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Maryland

In July 2017, PETA filed a lawsuit against the now-shuttered Tri-State Zoological Park of Western Maryland, Inc., a roadside zoo in Cumberland, Maryland, its principal Robert Candy, and a related organization, Animal Park, Care & Rescue, Inc. (collectively, Tri-State) for violating the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA). Tri-State confined and exhibited numerous species of animals including, during the relevant time, nine animals protected under the ESA: five tigers, two lions, and two ring-tailed lemurs. PETA’s lawsuit alleged that the defendants violated the ESA by unlawfully “taking” the ESA protected animals. Specifically, PETA alleged that Tri-State “harmed” and “harassed” the subject animals by confining them to wholly inadequate enclosures that were chronically littered with animal and food waste, and void of proper enrichment, denying the animals appropriate social groups, wholesome food, potable water, adequate veterinary care, and daily care by staff experienced in animal care and husbandry. PETA alleged that many of these conditions physically and psychologically harmed the animals and significantly disrupted their normal behaviors, in a way that put their physical and psychological well-being at risk of further injury.

Federal Court Denies Tri-State’s Motion to Dismiss, Excludes Tri-State’s Proffered Experts, and Grants, in Part, PETA’s Motion for Summary Judgment

Shortly after PETA filed suit, Tri-State unsuccessfully tried to dismiss the case by arguing, in part, that the federal Animal Welfare Act (AWA) “preempts, supersedes or nullifies” an action under the ESA for captive animals. The court rejected Tri-State’s attempt to escape liability under the ESA, making clear that the ESA “provides for separate and heightened protections for the subset of captive animals that are threatened or endangered.”

Following the close of expert discovery, PETA filed motions to exclude the improper opinion testimony of Tri-State’s three proffered experts, arguing that the purported experts were unqualified and that their opinions could not be supported with a reliable methodology. In a shocking example, one of the proffered experts maintained that her knowledge concerning the social needs of lions was based on sources such as Animal Planet’s “Big Cat Diaries.” Unsurprisingly, the court agreed with PETA and granted all three motions.

On July 8, 2019, in a first-of-its kind ruling, the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland granted in part PETA’s motion for summary judgment. Specifically, the Court found that the now-deceased tiger named Cayenne died due to the lack of basic veterinary care, and that such death constituted an unlawful “take” under the ESA. Cayenne, who began to “suffer from poor appetite and lethargy,” was anesthetized by Tri-State’s veterinarian, who admitted “lack[ing] any specialized experience or training in medical care for tigers.” Despite early complications (Cayenne went into respiratory arrest after being anesthetized) and the high risk of an adverse reaction during the anesthetic recovery period, Cayenne was left alone and unattended to recover from the anesthesia. Tragically, Cayenne suffered a heart attack and died.

PETA Prevails at Trial on All Theories of Liability

Following a six-day bench trial in November 2019, the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland found in favor of PETA “on all theories of liability” presented at trial, which exposed Tri-State’s “flagrant and persistent violations of the ESA.” In a scathing 46 page memorandum opinion, the court found that the trial evidence, which included eyewitness testimony, expert testimony, Tri-State’s records, and several photos and videos obtained by PETA, “overwhelmingly demonstrate[d]” that every protected animal at Tri-State had been unlawfully “taken” under the ESA—“harassed, harmed, or both in a most grievous fashion.”

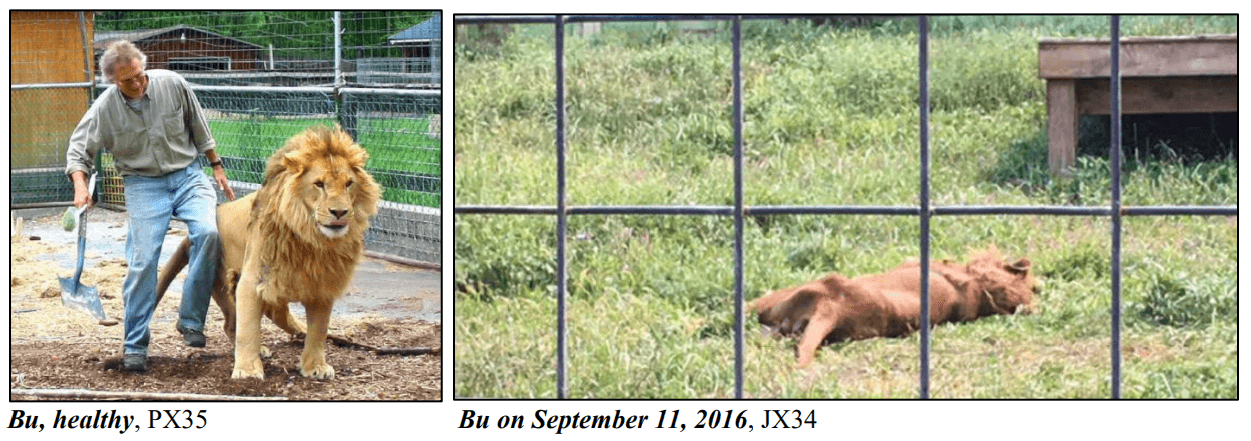

Lions: Mbube and Peka

With regards to the lions at Tri-Sate—Mbube and Peka—the court found that “Tri-State’s deplorable conditions” “harassed” the animals, who “lived in isolation” and were denied “social interactions [that] are integral to the well-being of lions.” Mbube and Peka were confined to barren enclosures, “exposed to harsh temperatures with little reprieve,” and were denied the opportunity “to engage in a wide range of normal social behaviors.” Tri-State further “harassed” Peka by failing to diagnose and treat her gait abnormality, a “longstanding condition [that] likely causes her chronic pain and interferes with species-typical behaviors.” Tri-State also “harmed Mbube, to the point of a painful death,” allowing him to die slowly “without any real veterinary care.” Mbube was “in dire physical straits,” yet Tri-State left him to suffer for months before “even notif[ying] a singular, patently unqualified veterinarian,” by which point he was “starving” and “emaciated.”

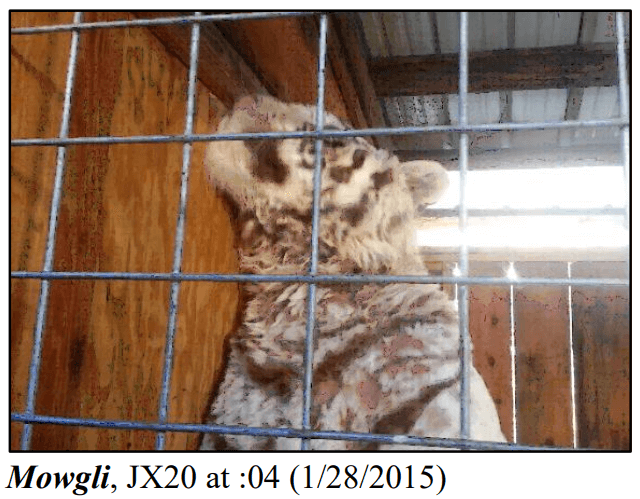

Tigers: Cayenne, Kumar, India, Mowgli and Cheyenne

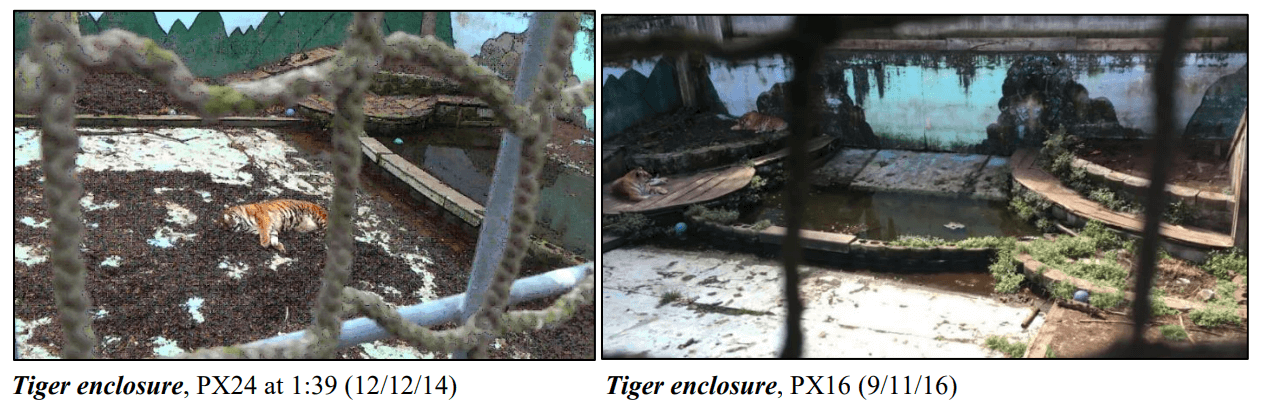

The court found that Tri-State “harassed” all five tigers in its custody—Cayenne, Kumar, India, Mowgli and Cheyenne—in part by holding them in “squalid living conditions” that were “so far removed from . . . accepted husbandry practices that they significantly disrupt[ed] a multitude of typical tiger behaviors and put the tigers at a high likelihood of injury.” Tri-State confined the tigers to a “dirty” and “dilapidated” concrete pit, which was formerly a swimming pool that it had divided into sections. The bottom of the pit held a reservoir of water that was “filthy, static, and filled with feces.”

The lack of sanitation created high risks for disease and infection, and, unsurprisingly, “at least two of the tigers . . . contracted diseases . . . consistent with unhygienic conditions.” The tiger enclosures lacked any meaningful enrichment or adequate shade, which further “deprive[d] the tigers of their ability to ‘engage in their natural behaviors.’”

Mirroring its finding at the summary judgment stage, the court found based on the evidence presented at trial that Tri-State “harmed” the tiger Cayenne, who “died due to the lack of basic veterinary care.”

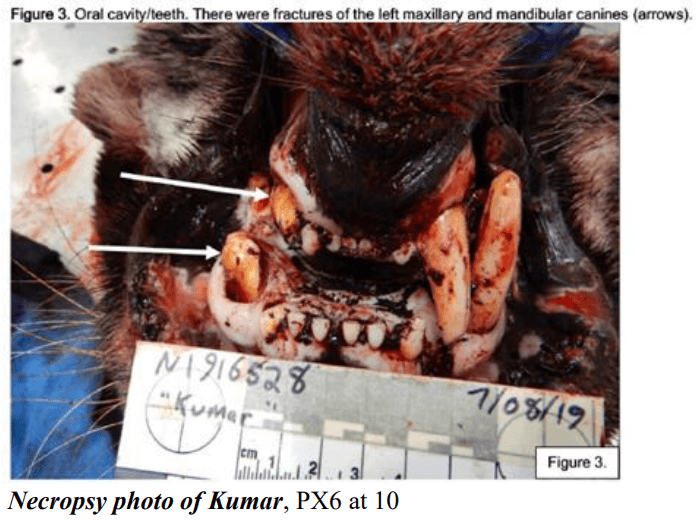

The court also found that Tri-State “harmed” and “harassed” the tiger Kumar by failing to treat his “broken, pulp-exposed teeth, ulcerated gums, and . . . punctured lip,” as well as his paws and hind legs, which were “pocked with ulcers,” all “while leaving him to languish in filthy surroundings.” It further “harmed” and “harassed” Kumar by failing to provide him with adequate veterinary care during the days leading up to his death. Kumar was not walking or eating, yet “received no adequate evaluation, treatment, or pain management, which unnecessarily prolonged whatever illnesses he endured.” Even when its own veterinarian “strongly recommended euthanasia,” Tri-State “chose . . . to let Kumar suffer.” Kumar’s necropsy revealed that he had been suffering from numerous issues including chronic and “consistently painful” oral ulcers, a “deep, penetrating [mouth] wound,” a distended colon, and “a two-centimeter-long tear and hemorrhaging in the membrane of his abdominal cavity.”

India too was harmed and harassed by Tri-State. While alive, she suffered from chronic (and preventable) flystrike; “[her] ears had been eaten [by flies] so badly and for so long that the veterinarian who performed her necropsy believed that her ears had been ‘surgically truncated.’” India died prematurely of “sepsis, an infection of colossal proportions not seen in cats in captivity,” that “[Tri-State] allowed . . . to ravage India” for “more than a month” while “expressly refus[ing] to secure medical treatment.” The sepsis also caused “myocarditis,” an inflammation of the heart, which left India to suffer and die while experiencing “daily pain ‘similar to a heart attack’ . . . ‘every time she took a breath.’” Given Tri-State’s failures, the district court found, that “[u]nquestionably [Tri-State is] directly responsible for India’s death.”

Tri-State also “harassed” and “harmed” the tiger Mowgli, who was “obese” with “flaccid” muscles. Mowgli was “in obvious discomfort” as evidenced by his constant rubbing “across deteriorating wood in his damp enclosure.” Tri-State left him to suffer “for years” with an easily diagnosable skin condition, and in the same environment as Kumar and India, “two victims of obvious painful infections.”

Lemurs: Bandit and Alfredo

The court further found that the lemurs—Bandit and Alfredo—were “subjected . . . to an onslaught of environmental assaults that harassed and harmed them.” The two lemurs were housed in an “isolating, barren, freezing, dirty, stress-inducing enclosure,” which deprived them “of almost all of their natural behaviors.” They were further harassed by being surrounded “with filth and a natural predator.” The chronically filthy conditions “disrupted their olfactory communication and their ability to scent-mark and put them at high risk of physical pain and permanent physical damage.”

Tri-State further “harmed” and “harassed” Bandit—who suffered from “untreated pain” stemming from a “protracted respiratory infection for nearly two years”—by “confin[ing him] to an environment that disrupted his normal behaviors leading to his self-mutilation, and . . . then fail[ing] to monitor, treat, and alleviate [his] life-threatening and ultimately fatal injuries.” Before his death, Bandit “exhibited signs of significant distress,” and did not receive “any [veterinary] examinations until the day of his death,” when he was “bleeding from [the] genital area” and hypothermic.

* * *

The court declared that Tri-State violated the ESA by unlawfully taking nine protected animals, and continued to violate the ESA by possessing the unlawfully taken surviving tigers and lion. The court entered an injunction prohibiting Tri-State from continuing to violate the ESA with respect to the animals at issue; permanently enjoining Tri-State from owning or possessing any endangered or threatened species; and terminating Tri-State’s ownership and possessory rights in the animals at issue. The court further ordered that Tri-State transfer ownership and custody of the surviving animals—with the exception of Alfredo, who was transferred to an Associations of Zoos and Aquariums–accredited zoo during the pendency of litigation—to The Wild Animal Sanctuary, a sanctuary accredited by the Global Federation of Animal Sanctuaries in Keenesburg, Colorado.

Tri-State’s request for a stay was denied, in part based on its finding that Tri-State’s “protracted and flagrant violations of the ESA render[ed] it likely that the remaining protected animals w[ould] be irreparably harmed were the Court to stay its order pending appeal.” The court further found that:

The public interest was “best served by ensuring that the remaining protected animals [were] not forced to endure life at Tri-State any further.”

—U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Following the Fourth Circuit’s denial of Tri-State’s motion for a stay pending appeal, the surviving animals were transferred to The Wild Animal Sanctuary.

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit Affirmed the District Court’s Judgment and SCOTUS Denied Cert Petition

Tri-State appealed the district court’s judgment, focusing primarily on the issue of whether PETA had standing to bring the ESA lawsuit. On January 29, 2021, in an unpublished per curiam opinion, the Fourth Circuit affirmed the district court’s judgment, finding that PETA had standing under the standard set forth in the seminal organizational standing case, Havens Realty Corp. v. Coleman, 455 U.S. 363 (1982). Specifically, the Fourth Circuit found that PETA had alleged and proved that it devoted resources in accordance with its mission-based requirement that it protect animals from abuse, neglect, and cruelty, to investigate and monitor Tri-State’s ESA-violative conduct, submit complaints to government agencies, and compile and publish information about Tri-State’s treatment of animals. The court also found that the roadside zoo’s “take” of ESA-protected animals “increased animals subject to abuse and created the misimpression that the conditions in which the animals were kept were lawful and consistent with animal welfare.” Because Tri-State’s conduct impaired PETA’s ability to carry out its mission and resulted in a drain on PETA’s resources, the Fourth Circuit upheld the district court’s ruling that PETA alleged and proved the requisite injury for the purposes of standing.

Tri-State’s petition for a writ of certiorari was denied on June 28, 2021.

Tri-State and its Counsel Sanctioned by District Court

On October 29, 2020, the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland ordered Tri-State and its counsel to pay PETA $56,655.77 in fees and costs in connection to a motion for sanctions that PETA filed after defendant Candy tried unsuccessfully to silence PETA’s investigators—who were also critical fact witnesses—days before the scheduled trial. Defendant Candy, with assistance of his counsel, swore out baseless felony criminal charges and falsely claimed that the district court had already found “probable” cause to believe that PETA’s investigators had violated the Maryland Wiretap Act. The court found Tri-State and its counsel “equally responsible” for their scheme that mislead the state court system to obtain criminal charges, and ordered defendants and their counsel jointly and severally liable for payment. The district court’s order was affirmed by the Fourth Circuit on January 6, 2022.

PETA Awarded Attorneys’ Fees and Costs

“PETA, as the subject-matter specialists, worked hand in glove with seasoned trial attorneys. The case was presented efficiently, cleanly, and professionally.”

—U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland

Under the ESA’s fee shifting provision, PETA filed motions for its attorneys’ fees and costs in both the district court and the Fourth Circuit. The district court awarded PETA attorneys’ fees, expert witness fees, and costs in the amount of $1,284,049.11. In so doing, the court noted that that the “case was presented efficiently, cleanly, and professionally,” and that “PETA’s comparatively thorough preparation likely secured its across-the-board success.” The Fourth Circuit awarded PETA the attorneys’ fees and nontaxable costs it incurred to defend the district court’s judgment in the amount of $57,949.28.

Together with the fees and costs associated with PETA’s motion for sanctions, PETA was awarded nearly $1.4 million dollars.