Ingrid Newkirk Turns 75 and Is as Radical as Ever

At most companies, if you get caught sending e-mails asking for naked pictures of your boss, you should probably start updating your résumé. At PETA, that’s just Monday.

Because our boss is the magnetizing firebrand of animal rights, the inimitable Ingrid Newkirk.

She’s disarmingly kind and soft-spoken, with proper British diction. But the gentle exterior belies guts of steel. Ingrid is always ready to make a bold statement, whether it’s stripping naked, setting fire to a car at an auto show, taking over Anna Wintour’s office, slapping a bumper sticker on a cop’s cruiser, or being dragged (literally) off to jail.

Here are just 10 attention-getting, courageous things that Ingrid has done in the pursuit of stopping cruelty to animals:

At 75 years old, Ingrid is still getting naked.

PETA is synonymous with “I’d Rather Go Naked Than Wear Fur.” But Ingrid would never ask her employees (or supermodels, actors, rappers, or athletes) to do anything that she wouldn’t do herself. She has stripped off her clothing countless times to protest fur, leather, meat, and more, and at 75 years old, she doesn’t plan on stopping anytime soon.

For one ad, she hung on a meat hook in a London market next to the bodies of dead pigs to show the striking similarities between humans and other animals.

“It was very cold,” she says, “and it was almost impossible to hang from that hook. It was very hard because you hold your whole weight on your hands. I just took everything off and grabbed it and hung on. I’m prepared for people to say that they find the billboard offensive. Animals are just like us in body and experience the same feelings. Sometimes people just need to think about it. I was thinking we should have the sound of the pigs (in the slaughterhouse), but it would really be too much.”

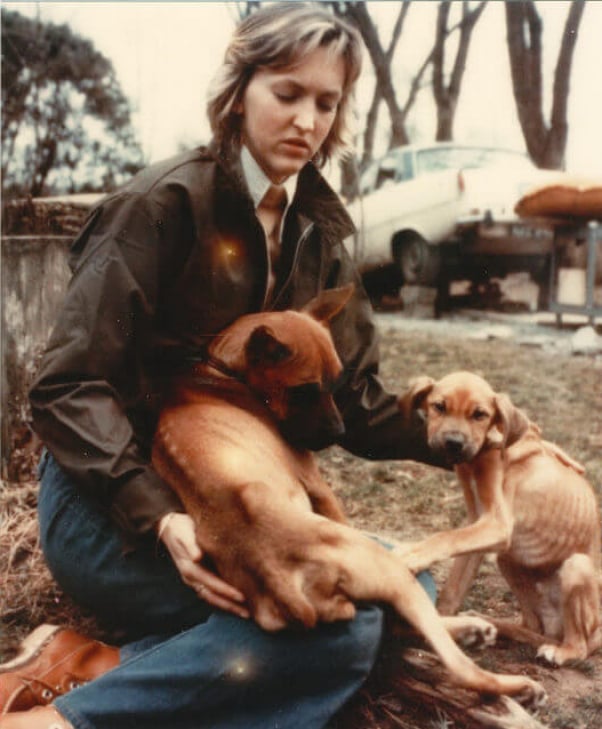

She created Washington, D.C.’s, first spay/neuter clinic and adoption program and stopped the sale of animals from shelters to laboratories.

It may not sound revolutionary now, but in the 1970s, spay/neuter clinics and shelter adoption programs were uncharted territory. As D.C.’s first female poundmaster, Ingrid got legislation passed to secure public funding for spay/neuter services and veterinary care. She ended the sale of animals to laboratories and established the shelter’s adoption program for homeless animals. For those efforts, she was chosen a Washingtonian of the Year.

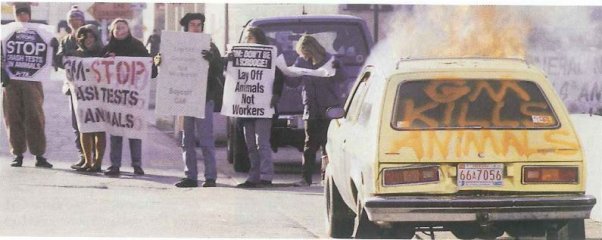

She set fire to a car outside a General Motors auto show.

GM was the last automaker using primates, pigs, dogs, ferrets, mice, and rats in cruel car crash tests and was refusing to work with PETA to implement humane test methods, such as using computerized mannequins. So PETA members began demolishing donated GM vehicles with sledgehammers outside company events and handcuffing themselves to cars at auto shows. Celebrities refused to do GM commercials, and our members pledged never to buy the company’s cars. In any country in which GM held an event, PETA was there. During one protest, crowds gathered as Ingrid set fire to a car that members had donated to the cause. She did it again at two more shows. After 18 months of PETA’s headline-making stunts exposing GM’s cruelty, the automaker ended all car crash tests on animals, and the entire practice was stopped worldwide.

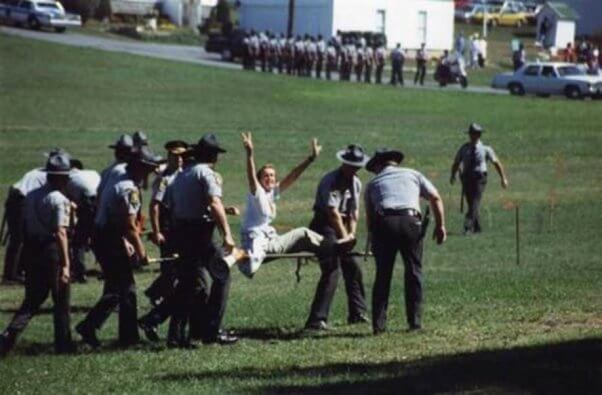

She defiantly spent 15 days sitting in jail in order to cost a town money.

The town of Hegins, Pennsylvania, hosted an abhorrent annual pigeon shoot in which 5,000 birds were trapped and confined to tiny cages for two days without food or water before the sick, weak, and disoriented animals were released so that participants could shoot at them. Those who were wounded but didn’t die instantly crashed to the ground—children of the shooters would then stomp on them or twist off their heads. In 1992, about 2,000 animal rights activists protested the event. Ingrid led 40 of them onto the field to stop the shooting, grab boxes of birds before they could be released, and scoop up the wounded ones. When they were arrested, they decided that instead of paying the fines, they would sit in jail in order to force the town to pay the cost of keeping them there, with the goal of making it too expensive for the city and state to pay for security and jail stints related to the pigeon shoot.

The 1992 pigeon shoot cost taxpayers $300,000, and the event was soon cancelled.

She ripped up a leather jacket at Gap.

After Ingrid investigated the leather industry in India and found that workers break cows’ tails, rub chili peppers into their eyes, and much more, PETA presented the evidence to retailers and asked them not to obtain leather from either India or China. Gap refused, so PETA launched a full-scale campaign that included Ingrid and Chrissie Hynde taking over the window display at the company’s New York flagship store. Ingrid pulled apart a leather jacket and pointed out to the crowd that had gathered outside that whip marks were still visible on the animal’s hide. Shortly afterward, Gap stopped purchasing leather from India and China, and J.Crew and Liz Claiborne followed suit.

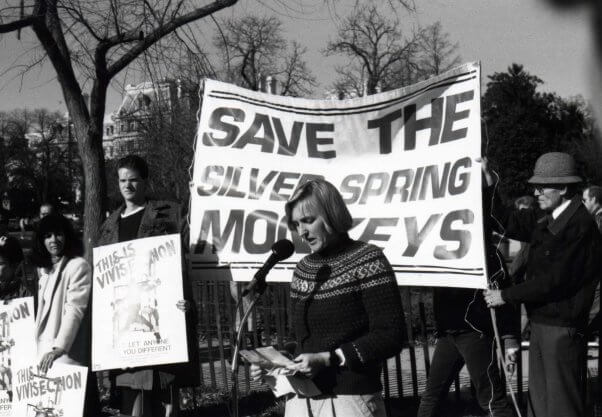

She made “animal rights” a household term with the first-ever eyewitness investigation: the Silver Spring monkeys case.

In the summer of 1981, Ingrid and another PETA founder set out to expose the horrors that animals endure in laboratories, with the first eyewitness investigation in the animal rights movement. Ingrid’s colleague took a job at the Institute for Behavioral Research, a federally funded laboratory in Silver Spring, Maryland, where monkeys’ spinal nerves were severed, rendering one or more of their limbs useless. Through the use of electric shock, food deprivation, and other methods, the animals were forced to try to regain the use of their impaired limbs.

As expert witnesses entered the laboratory at night, Ingrid kept watch from a cardboard box in the parking lot, with a walkie-talkie in her hand to alert them if anyone approached. When the photos and video footage of the Silver Spring monkeys were released, it ignited a media firestorm and thrust PETA, animal rights, and the cruelty of experimentation onto televisions and into newspapers across the country.

This groundbreaking investigation led to the nation’s first arrest and criminal conviction of an animal experimenter for cruelty to animals, the first confiscation of abused animals from a laboratory, and the first U.S. Supreme Court victory for animals used in experiments. It even led to landmark additions to the Animal Welfare Act—and public scrutiny of the abuse that animals endure in experimentation. It also proved the power of using eyewitness investigations in advocating for justice, a right that PETA’s legal team is now defending as it fights corporate interests that are trying to criminalize such investigations.

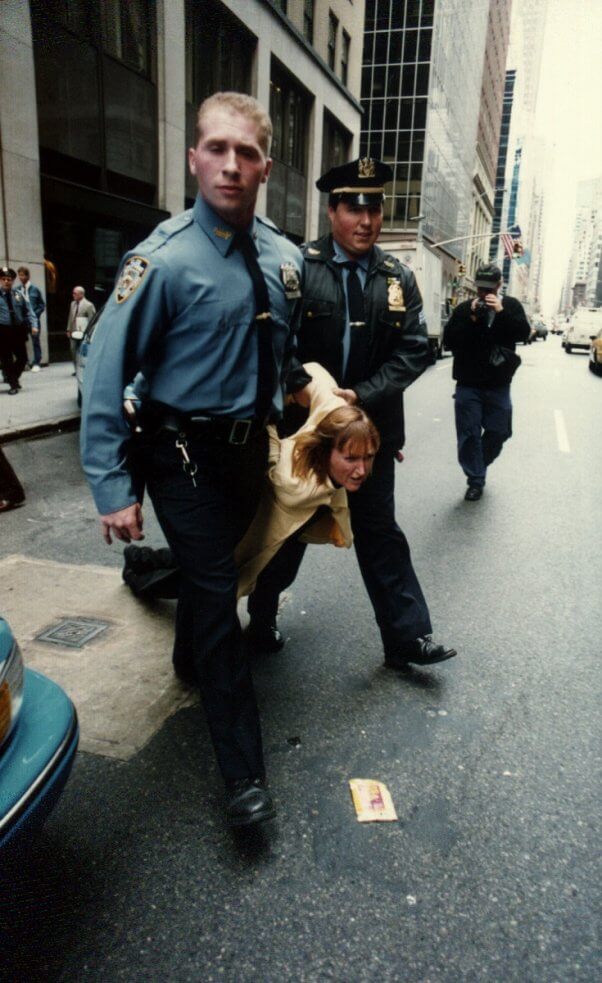

She slapped a “Meat Stinks” sticker on a police cruiser.

As police officers were eating dinner in a diner, Ingrid saw an opportunity and slapped a “Meat Stinks” bumper sticker on the back of one of the police cruisers. Another officer drove up, caught her, and promptly hauled her off to jail. But beloved civil rights attorney Philip Hirschkop (of Loving v. Virginia fame) argued that she was simply exercising her right to freedom of speech, and the sympathetic judge just as promptly dismissed the case.

She had herself strapped to a horse-drawn carriage and pulled it through the streets.

Ingrid had herself hitched to a horse-drawn carriage with a bit in her mouth and let residents of Mumbai watch her struggle to pull it through the streets in the hot sun, just as horses are forced to do. Because of PETA campaigns, Mumbai and other cities around the world—the list continues to grow—have banned horse-drawn carriages.

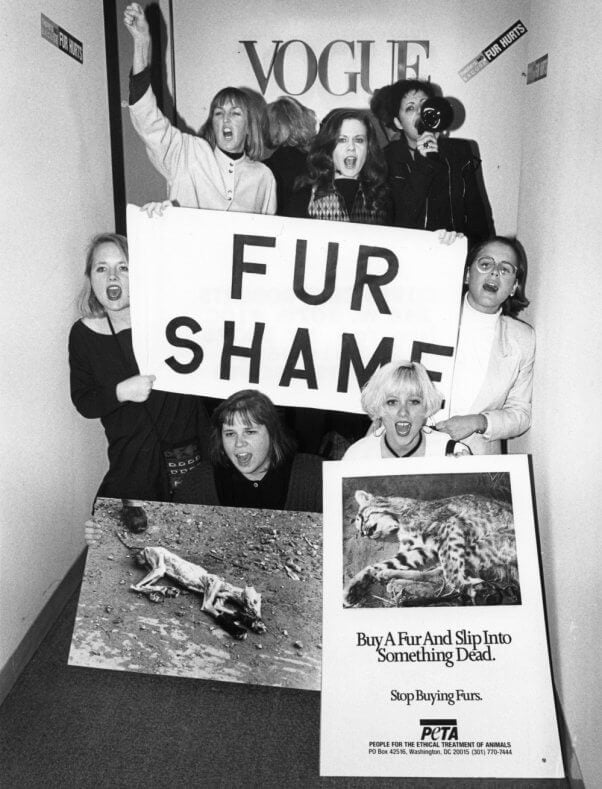

She took over Anna Wintour’s office and answered her phone.

One can only waste so many good pies on Vogue editor Anna Wintour. So Ingrid and PETA members, together with Kate Pierson of The B-52’s, finagled their way past security and crashed into the magazine’s New York office to protest its use of fur. When Wintour ran and barricaded herself in a back room, Ingrid took over the reception desk and began answering Vogue‘s phone by saying, “We’re closed today due to cruelty.”

Upon her death, her body will be used for a human barbecue.

Even after she’s gone, Ingrid is still going to be grabbing headlines and making waves for animals. Her unique will directs that her various body parts be used to help end animal suffering, including that her flesh be used for a human barbecue and her skin be made into purses and other leather products to show that all animals have the same parts and none wants to be killed to become a nugget or a shoe.

The lizard tattoo on Newkirk’s arm will become a real—but 100% cruelty-free—“lizard skin” purse. A watchful eye will be sent to the National Institutes of Health because it needs to know that PETA will be constantly watching. Her liver will be publicly displayed in France to protest the force-feeding of geese and ducks for foie gras.

An ear to King Felipe VI of Spain … her lungs to the governor of Alaska … a piece of her heart to Elon Musk: Talk about putting your whole self into some final wishes!

Why the attention-getting antics? Well, you’re not reading an article titled, “Ingrid Newkirk Turns 75 and Is Still Having Meetings With Companies,” are you? (Although she does plenty of that, too, of course.)

“Our mission is to provoke thought,” she believes. “People have been taught to disregard what happens to pigs, chickens, monkeys, rats, bears, and horses and not to think about the suffering they go through. Our job is to get people’s attention and make them think. We’re not out to be popular.”

And yet PETA is the largest and most effective animal rights organization in the world.

Feeling inspired?

Join PETA’s Action Team to hear about upcoming events near you and more ways you can help animals.