Experiments on Animals Don’t Help Humans Who Struggle With Addiction

What Is a Substance Use Disorder?

A substance use disorder (SUD) occurs when someone is using one or more substances in a way that affects their brain chemistry and behavior, impairing their ability to stop or regulate their use of the substance(s). SUDs may keep using the substance(s) despite negative consequences, such as poor health outcomes, relationship difficulties, or problems at work. Addiction is the most severe form of SUD.

People suffering from SUDs may struggle with alcohol and other depressants, opiates and other narcotics, tobacco products, cannabis, or stimulants, such as cocaine and methamphetamine.

How Many People Have SUDs?

According to the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health, “In 2020, 40.3 million people aged 12 or older (or 14.5%) had an SUD in the past year, including 28.3 million with alcohol use disorder, 18.4 million with an illicit drug use disorder, and 6.5 million with both alcohol use disorder and an illicit drug use disorder.”

It’s common for individuals with SUDs to have other mental health conditions, such as anxiety, depressive disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and schizophrenia, among others. Sometimes individuals develop SUDs when attempting to self-medicate these co-occurring conditions. Genetics may also be a risk factor for SUDs.

SUDs can happen to anyone, regardless of age, sex, race, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status.

How Are SUDs Treated?

SUDs are chronic, treatable conditions, but only about 10% of people who need treatment receive it.

The most common treatment for SUDs is behavioral therapy, which may occur privately or in a family or group setting. Individuals may undergo outpatient counseling or inpatient rehabilitation in a full-time facility. Medications that reduce craving for and/or blunt the effects of substances (making them less appealing), such as naltrexone, buprenorphine, methadone, disulfiram, or acamprosate, may also be available for individuals with alcohol and/or opioid use disorders.

What Happens During Substance Use and Addiction Experiments on Animals?

Such experiments on animals often involve forcing them to ingest substances via laced water, injection, or forced inhalation.

For example, experimenters injected Japanese quails with methamphetamine, watched them have sex, and then forced them to undergo drug withdrawal. Others injected baby rats with ketamine and ethanol. You can even see how they described their “work” in their own words. (Warning: it’s not pretty.)

Other animals used in SUD experiments are forced to administer drugs to themselves. In some self-administration protocols, an experimenter performs surgery on an animal to insert a catheter into their jugular vein. This catheter is attached to a tube through which cocaine or other drugs are infused when the animal pushes a lever. The drug then enters directly into their bloodstream.

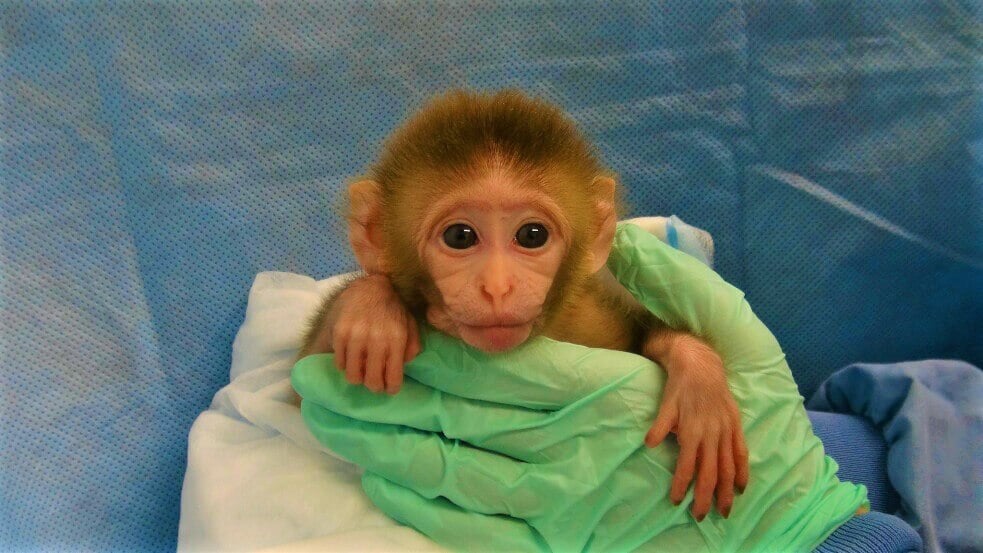

In recently published studies on monkeys, experimenters trained animals to self-administer fentanyl and heroin and to binge drink ethanol and inject themselves with cocaine.

Making Animals ‘Addicted’ in Experiments Doesn’t Help Humans Struggling With Addiction

Humans with SUDs have vastly complex experiences that can’t be simulated by using animals in a laboratory setting. Key components of addiction, such as social and environmental factors and language, are fundamentally impossible to model in nonhuman animals. This is partially due to the bleak, extremely limited, and species-inappropriate conditions in which experimenters keep animals in laboratories. According to experts, “it is difficult to argue that it truly models compulsion, when the alternative to self-administration is solitude in a shoebox cage.”

And when experimenters give the animals used in SUD experiments the rare opportunity to decide for themselves, many of them choose sugar or social interaction over the drug being studied. Even among animals with very heavy previous drug use, only about 10% continued to give themselves a drug when they had the option to make another rewarding choice, which is not typically true of humans who suffer from SUDs.

Because animals are poor models for human SUDs, their use has failed to produce treatments to help humans with this condition. There isn’t a single medication available to treat stimulant use disorders, despite many experiments on animals intended to help develop one. The therapies available for smoking, alcohol use, and opioid use were developed primarily from clinical observations of humans rather than experiments on animals.

Human-Relevant SUD Research and Treatment Is Needed

Human-relevant methods, like those detailed below, can provide researchers with answers they’ll never get by torturing other animals.

Scientists at the University of Connecticut are using stem cells donated by alcoholic and non-alcoholic human subjects to study the effects of alcohol on a specific receptor in the brain. Their results were at odds with some of the findings from experiments on animals.

A type of human stem cell that can be collected non-invasively from patients with SUDs and other accompanying conditions has been used to model these disorders, opening the door to drug discovery and new precision medications.

Human brain imaging has also been used to study the brain circuitry of individuals with SUDs.

The funds currently used to support ineffective substance abuse studies on animals must instead be used for human-relevant, non-animal research and to aid human-relevant drug prevention, rehabilitation, and mental health programs.

For an accurate diagnosis of suicidality, depression, alcohol problems, or other mental illnesses, consult a qualified healthcare professional. If you are in crisis or think that you may have an emergency, call your doctor or 911 immediately. If you’re feeling suicidal, thinking about hurting yourself, or concerned that someone you know may be in danger of hurting themselves, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988. This free service is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and is staffed by certified crisis-response professionals. If you’re located outside the U.S., call your local emergency line immediately.