When Three Years Feels Like an Eternity

Feld Entertainment, the private company that owns Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, recently announced that it plans to phase out its use of elephants in performances by 2018. But why does this billion-dollar behemoth need three years to do what it should do immediately?

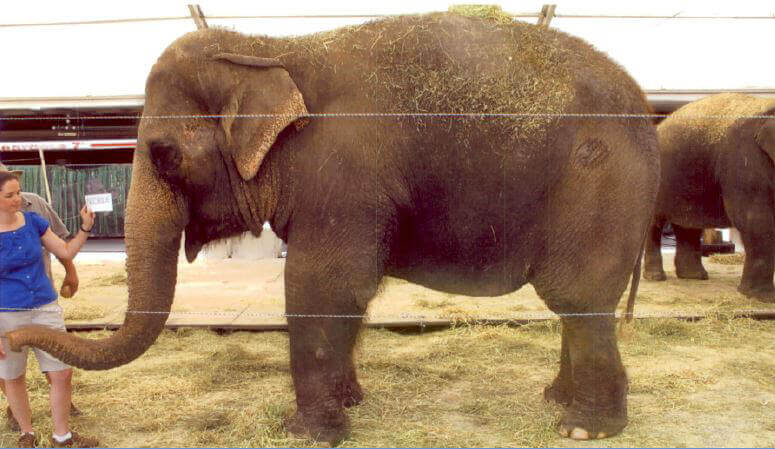

A company spokesperson acknowledged that the decision was reached because the public has made it clear that it no longer supports forcing elephants to perform. More and more people have come to learn that in circuses, baby elephants are taken from their mothers, beaten into submission with bullhooks and shackled for the rest of their lives. A bullhook is a heavy baton with a sharp metal tip and hook on the end used to keep captive elephants submissive and afraid. The company’s CEO, Kenneth Feld, admitted that the bullhook bans being passed or considered in cities throughout the country contributed to the decision.

So why force elephants to live in fear of being hit with these weapons and to spend days on end confined to fetid boxcars for another three years? If the company is serious and sincere about evolving, then it should make this change now.

Transported from venue to venue almost year-round, elephants used by circuses spend most of their lives shackled and confined. These animals, who are genetically designed to walk many miles every day, must eat, drink, sleep, defecate and urinate in a world measured in inches. This prolonged chaining is linked to deadly foot disorders, arthritis and “stereotypic” (neurotic) behavior, such as constant swaying.

At least 11 elephants with Ringling have tested positive for tuberculosis (TB)—and that’s no laughing matter. TB can be deadly and is highly transmissible from elephants to humans, even without direct contact.

According to Kenneth Vail, the Animal Welfare Act compliance officer for Feld Entertainment, TB is “probably going to be the downfall of Feld’s elephants.”

Many elephants did not live long enough to benefit from Ringling’s change of heart. It’s too late for an 8-month-old baby elephant named Riccardo, who was destroyed after he fractured his hind legs when he fell from a pedestal during a training session; 4-year-old Benjamin, who drowned while being pursued by a handler with a bullhook; and 3-year-old Kenny (Kenneth Feld’s namesake), who died shortly after he was forced to go on stage despite the fact that he was bleeding from his rectum and having difficulty standing.

While Ringling’s decision will provide some relief to elephants forced to perform, let’s not forget that at its Florida compound, elephants are shackled and handled with bullhooks, so a serene retirement does not await them. They are also used as breeding machines, even though captive elephants are dying at a faster rate than they are breeding. Ringling has failed to make any meaningful contribution to the protection of wild Asian elephant habitat and has been unabashedly uninterested in furthering conservation of wild elephant populations. When asked why it doesn’t redirect its efforts from captive breeding to wild habitat conservation, Ringling’s national media representative responded, “Habitat is another thing. We’re not a conservation organization.”

Instead of breeding more elephants who will spend their lives in chains and in forced breeding regimens, Feld Entertainment could transform its Florida facility into a genuine sanctuary—modeled after the successful examples of California’s PAWS and Tennessee’s The Elephant Sanctuary—where elephants could form social groups of their own choosing, swim in ponds and roam over large areas to forage and explore.

Feld Entertainment is on the cusp of a new business model. The company just needs to go further—and faster.

By Delcianna Winders, deputy general counsel for the PETA Foundation