Here’s Everything Animal Experimenters Don’t Want You to Know About Craniotomies

Laboratory lingo often doesn’t tell the whole story. Experimenters go to great lengths to hide the true nature of their work through euphemisms and multisyllabic mouthfuls. They think of animals as “test subjects,” not as living, feeling beings. They somehow don’t hear cries of pain but “vocalizations.” And rather than saying they kill animals, they say animals are “sacrificed,” “terminated,” or “euthanized.”

You may hear that an experimenter is “studying” animals’ brains. What you won’t hear is that they’re sawing open animals’ skulls, injecting toxins into their brains, and bolting equipment onto their skulls before killing and dissecting them.

This type of “study” seems innocuous enough because experimenters casually summarize it with one clinical term: “craniotomy.” And then they move on, as if it’s as normal as breathing.

It’s not.

Craniotomy 101

Craniotomies are major invasive surgeries that involve slicing through layers of skin and muscle of an animal’s head, sawing out a piece of the skull, and cutting through even more tissue to expose the brain. Throughout the surgery, animals are immobilized in a device while experimenters poke around inside their head.

The archaic surgery is performed with common hand-held tools such as electric drill bits and saws, which cause considerable damage to brain tissue and the surrounding network of nerves and blood vessels. Animals who survive the surgery are left with lifelong traumatic brain injuries and significant brain changes. All too often, the animals receive inadequate pain relief after these harmful surgeries.

Millions of Victims

Records of the number of craniotomy procedures performed are not formally kept, but after analyzing thousands of published research papers, PETA estimates that more than a million animals have endured craniotomies over the last 30 years. That means thousands of animals—including dogs, cats, mice, monkeys, and others—are being subjected to the surgery each year.

And it’s being done at nearly every institution that experiments on animals, including most commercial laboratories and major research universities.

Step One in a Torturous Procedure

Craniotomies are the first step experimenters use when they want to damage animals’ brains in experiments. The surgery allows experimenters to implant electrodes, inject chemicals, induce a stroke by damaging blood vessels through transcranial occlusion, inject cancer cells into animals’ brains to induce the formation and growth of tumors, and more.

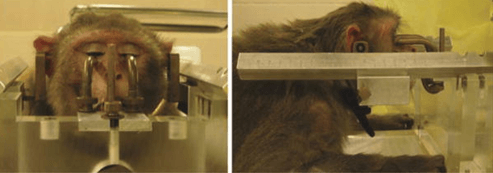

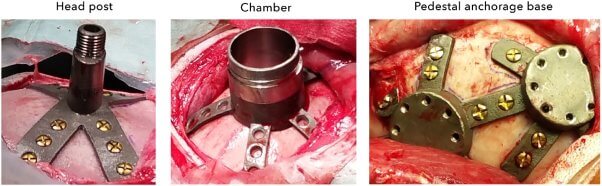

Craniotomies also provide access points so that experimenters can insert metal posts and chambers into animals’ heads. Experimenters use headposts to screw animals directly into restraint chairs, where they’re locked in place and held completely still for hours at a time, denied food and water, and forced to complete a battery of tests. Chambers are used as an entry point to the brain, allowing experimenters to poke around inside while they insert electrodes and implant devices that alter brain activity.

To bolt down the invasive equipment, experimenters peel back layers of flesh and drill screws directly into animals’ exposed skulls. Devices are permanently secured with a liquid glue known as “bone cement.”

Deadly Infections

Unsurprisingly, the brain doesn’t respond well to having cement poured on it. Bone cement is known to cause inflammation, infection, tissue damage, and bleeding. It can also leak into the body, causing painful toxic effects in bones. There are other, less catastrophic adhesive options, but experimenters opt for bone cement simply to pinch a few pennies.

A University of Pennsylvania study found 13 different pathogens in skull implants, including infectious diseases that can be transmitted to humans. These infections spread like wildfire throughout the brain, turning the skull into a painful thin, soft sponge. Infections often lead to complications, which can result in even more painful surgeries for animals and sometimes even death.

Bad Science That Isn’t Helping Humans

Experimenters can poke around in the heads of millions of animals and still not learn a single useful thing about human brains.

Human brains are vastly different from the brains of other animals, and human afflictions, including strokes and head injuries, cannot be accurately studied using them. The brain damage and infections caused by craniotomies also corrupt any data collected from the experiments.

Relying on animal experiments is hindering progress in human medicine. Approximately 90% of basic research, most of which involves animal experiments, fails to lead to treatments for humans. And according to the National Institutes of Health, 95% of new drugs that are shown to be safe and effective in animals fail in human clinic trials This is because most of those drugs don’t work in humans or actually turn out to be dangerous. What’s more, animals are heavily used in preclinical studies, and up to 89% of those experiments can’t be reproduced.

Better Options Exist

Researchers can study human brains directly with advanced modern technology. Neuroimaging techniques, including common MRI and PET scans, provide accurate and detailed visual models of the brain’s structure and activity. In vitro methods, including three-dimensional brain models and brains-on-a-chip, can replicate brain functions and allow researchers to study brain development, disease modeling and treatments, and drug discovery.

Human brain tissue from volunteers also provides researchers with valuable material that can be used in a variety of tests.

What You Can Do

Superior animal-free research methods can provide human-relevant data without killing animals. That’s why PETA’s scientists developed the Research Modernization Deal, which outlines a comprehensive strategy for replacing all animal experiments with more effective, human-relevant, non-animal methods.

Please TAKE ACTION by urging your U.S. legislators to support PETA’s Research Modernization Deal:

And everyone, no matter where you live, can take action below for monkeys abused in cruel fright experiments: