Read All About It! How PETA Scientists’ Published Papers Promote Animal-Free Testing

Regulatory agencies around the world require that any new method for testing the toxicity of chemicals first be evaluated for its scientific usefulness before companies and regulators can apply it. Up until recently, this process included measuring a new method’s accuracy by directly comparing its results to those from tests on animals—even though many such tests aren’t reliable or relevant to humans. But an exciting new paper coauthored by PETA Science Consortium International e.V. and scientists from government agencies could help change this process and increase the speed at which modern, non-animal tests are adopted.

The paper, published in Archives of Toxicology, provides regulators with a different way to establish scientific confidence in new methods—one that’s grounded in human biology rather than flawed tests on other animals. The use of this framework would accelerate the uptake of relevant, reliable, non-animal test methods, leading to improved protection of human health and preventing animals from being subjected to tests in which they are forced to ingest or inhale or are injected with toxic substances before being killed.

The Science Consortium routinely collaborates with experts from regulatory agencies, industry, and academia to publish papers in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

These papers have shown how modern, non-animal approaches can be used to test chemicals instead of relying on archaic and crude experiments on animals. These publications capture the current thinking of leaders in the regulatory field and build support for the acceptance of superior, animal-free methods.

And the work doesn’t stop once a paper lands in a scientific journal. PETA scientists present their findings at high-profile conferences and meetings around the world, ensuring that as many people as possible understand the benefits of non-animal testing approaches.

A History of Publications by the Science Consortium

Over the years, PETA scientists have published dozens of papers on topics affecting animals used in regulatory testing. Here are just a few examples:

-

Dietary testing on birds

The Science Consortium and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published a paper that led to a new EPA policy preventing hundreds of mallards and quail each year from being used in tests in which they’re fed pesticide-laced food for days before being killed. The paper came after the authors reviewed 20 years of data and finding that the agency could confidently protect the environment without poisoning birds in this cruel test.

-

Eye testing on rabbits

In another collaboration between the EPA and other international experts, a Science Consortium publication showed that approaches that don’t use live animals to test whether chemicals irritate human eyes were as, if not more, reflective of human biology than tests in which chemicals are applied to the eyes of live rabbits—and that their results are more consistent. The paper concluded that the newer methods should be accepted now to replace the rabbit test, which would prevent an estimated 600 rabbits from being used in pesticide tests each year in the U.S. alone.

-

Antitoxin production in horses

The Science Consortium published a paper on a groundbreaking project (which it funded) that led to the creation of fully human-derived antibodies capable of blocking the poisonous toxin that causes diphtheria. These human-derived antibodies are the first steps toward ending the 100-year-old method of injecting horses repeatedly with the diphtheria toxin and then draining huge amounts of their blood in order to collect the antibodies that their immune systems produce to fight the disease.

-

Cancer testing on rats and mice

A Science Consortium publication detailed a new approach to assessing chemicals for their potential to cause cancer. It was developed in collaboration with scientists from government, academia, and industry and is already being used to spare hundreds of mice and rats tests in which they’re fed pesticides every day to see if tumors develop.

-

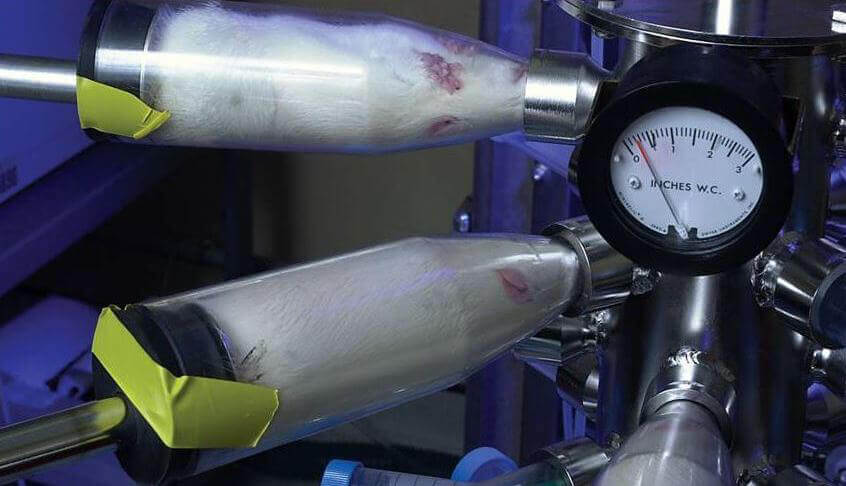

Inhalation testing on rats

Funding from the Science Consortium helped create a first-of-its-kind human cell–based three-dimensional lung model that can be used to study the effects of chemicals and other substances on the deepest part of human lungs. Together with other non-animal tests, this model has the potential to help replace the use of roughly 1 million animals each year in tests in which they’re confined to small tubes and forced to inhale substances before being killed. The Science Consortium published a paper describing this promising lung model in an esteemed scientific journal.

-

Pyrogen testing on rabbits

To test medical devices for pyrogens—contaminants that cause fever in humans—the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires either a test in which rabbits are injected with test substances and restrained for hours while their body temperatures are taken or one in which horseshoe crabs are collected from the wild and bled, a process that has led to a serious decline in their populations.

The Science Consortium worked with government agencies to organize a workshop on using non-animal methods for pyrogen testing and published the results. The Science Consortium is now using the input from that workshop to conduct the testing needed to show regulatory agencies like the FDA how a non-animal method can be used to test medical devices for pyrogens.

-

Cell culture research without calves

The Science Consortium published a paper showing how to maximize the quality of cell-culture research by using an animal-free medium instead of highly variable fetal bovine serum (FBS). Every year, up to 1.8 million unborn calves are killed worldwide to produce FBS—a mixture of molecules, including hormones, proteins, and growth factors, obtained from the blood of fetal calves after their mothers are slaughtered for food. The paper describes the successful transition of a human lung cell line commonly used in research to cell culture media without FBS or any other animal-derived components, setting a precedent for making the same transition for other cell types.

Along with conducting research and authoring publications, the Science Consortium organizes free webinars, sends students and early-career scientists to important scientific conferences and meetings, and provides free brochures and factsheets. It’s all part of an overall effort to ensure that researchers have the latest information, education, and training they need to implement and advance the use of non-animal test methods.