Did You Ride an Elephant? See Where She Was Probably ‘Trained’

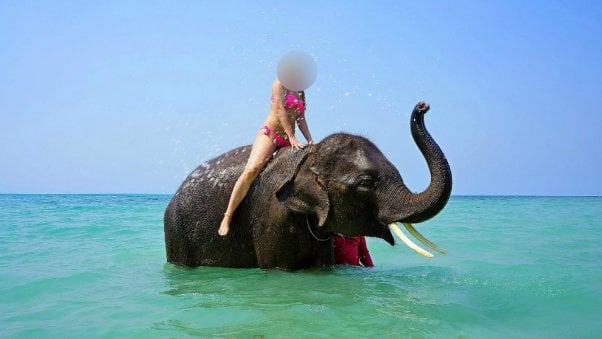

Many of us have seen elephants being used to give rides: heavy saddles on their backs, chains around their necks and ankles that handlers can pull, and the ever-present bullhook in the trainer’s hand, always within striking distance. As they plod back and forth on a worn patch of ground, people line up for a turn to climb onto the massive animals’ backs and have their pictures taken.

But how did they get there?

Elephants don’t voluntarily trade their forests and families for chains and a lifetime of servitude. They’re usually captured from the wild as babies, torn away from their distraught mothers, and “trained” at highly secretive elephant training camps, like those journalist Liz Jones went inside in India. What she found is extremely disturbing.

Here is just some of what Jones witnessed inside the elephant training facilities:

“Then one of the elephants, Nandan, a 43-year-old tusker, or male, begins to bellow and struggle against the chains that bind his hind feet to a stump and his front legs to a tree, cutting into his flesh. He cannot lie down. He cannot stretch out his hind legs. . . . ‘How long has he been chained like this?’ I ask Prof Nameer. ‘He has been chained in that spot, never released even for an hour, for 20 years,’ he replies.”

“Tears stream from the blinded eye of one elephant.”

“Sudhakar tells me a common practice is to insert a nail above the elephant’s toe. The wound heals over. If the mahout wants total obedience, all he has to do is press that button.’”

“They are routinely temporarily blinded, to make them wholly dependent on the mahout.”

“The only food given here is dry palm leaves. An elephant in the wild will eat a wide variety of grasses, fruit, leaves and vegetables. In the wild, an elephant will drink 140 to 200 litres of water a day. Here, they are lucky if they get five to ten.”

“Pajan means that, having been isolated, confined, starved, dehydrated and kept awake by noise, each morning and evening the elephant is beaten with poles, for up to an hour. For six months.”

“I walk past baby elephants, so inquisitive, and see one get beaten with an ankush—a stick with a metal hook on the end; all the baby was doing was coming to say hello.”

“They have no shade, no free access to water. They have been beaten for an hour, twice a day, every day. I look into the eye of the poor creature on the right. He knows what is about to happen to him. A mahout raises his arm, and lands a blow on his head: the hollow sound is the most chilling I’ve ever heard. The elephant squeezes his eyes shut, and tears run down his face.“

“Of all the animal abuse stories I have covered in the past 30 years, this is by far the worst.”

“Has every elephant you see giving rides in festivals, on safari, been through this process? ‘Yes.’”

Jones visited the training camps in 2015. Orders were pouring in for elephants. If you have ridden an elephant anywhere in the world, he or she was likely trained in one of these facilities or one that uses similar methods to break the animals’ spirits and make them terrified and submissive.

And if you’re thinking that the abuse stops once the elephants’ spirits are broken, you’re wrong.

What fuels this extreme violence and abuse? Tourist dollars.

Elephant ride operators and the training camps that supply them will close when they stop making money. Please, never support elephant attractions. Most of the ones that bill themselves as “sanctuaries,” “rehabilitation centers,” and “orphanages” are lying to you. And tell the travel companies that are still offering elephant rides that you won’t be a patron until they join dozens of competitors in taking a stand against cruelty to elephants.