Lolita’s Suffering Is Over

Lolita has died. Her miserable existence at the Miami Seaquarium—for interminable days, years, and decades—is finally over. Earlier this year, during a news conference held in Miami on March 30, the Miami Seaquarium announced plans to release the long-suffering Lolita (aka “Tokitae,” “Toki,” and “Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut”) to a seaside sanctuary in Washington state.

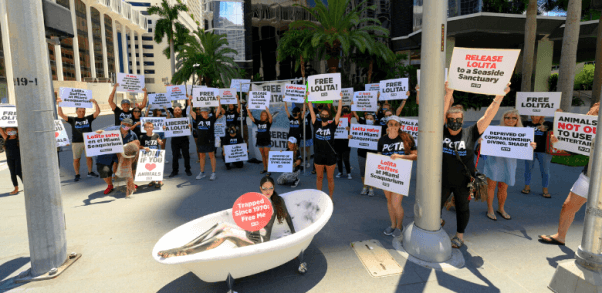

This announcement followed a massive campaign by PETA—which pursued several lawsuits on her behalf—and local residents and celebrities who raised awareness of her plight through dozens of protests as well as The Dolphin Company’s partnership with Friends of Toki. This plan, though it never came to fruition, had been made possible through the generosity of philanthropist Jim Irsay, owner and CEO of the Indianapolis Colts.

Lolita was only about 4 years old when she was torn away from her family and ocean home during the largest capture of wild orcas in history.

Perhaps it’s a blessing that she had no way of knowing that she’d spend the next half-century in the smallest orca tank in the world, never to see her family again. The value that the Seaquarium placed on this young orca’s life? It paid $6,000 for her. Of the seven orcas taken from their home during that round-up, Lolita was the last survivor. The orca believed to be her mother, who is apparently still swimming in nature, has likely outlived her.

It was 1970 when teams used speedboats, airplanes and explosives to corral the entire Southern Resident orca community—numbering 80 members—into a narrow cove. Four drowned, and seven young ones were removed and sold to aquariums around the world. First named “Tokitae”, Lolita suffered in a tank smaller than any other that had ever been used to imprison an orca for life, which was not just cruel but also illegal, according to the federal Animal Welfare Act. The plan to move her to a seaside sanctuary came too late, and she languished in her hellish prison until the day she died.

For more than 50 years, Lolita saw nothing but the concrete walls surrounding her. Her only orca companion was Hugo, another unfortunate who had been netted and removed in the round-ups. He railed against captivity, routinely banging his head against the walls and even once severely cutting himself when he broke the glass of a viewing window. Finally, in 1980, he rammed the wall of the tank so hard that he died. The official report said that he had died of a brain aneurysm. Hugo had taken decisive action to end his suffering, but now Lolita was alone.

Day after day, year after year, decade after decade, Lolita performed her sad and desultory tricks. She called out to her lost family, using the dialect unique to her pod. Orcas have keen memories. No doubt she thought about her mother and siblings and longed for the days when she could swim free and dive deep. Lolita’s Southern Resident family has been classified as endangered, and the government agreed with PETA as well as the Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Orca Network that Lolita should be included in her family’s Endangered Species Act classification. Plans were finally underway to send her home, but she didn’t make it.

It’s too late for Lolita, but it’s not too late for other captive orcas, like those in SeaWorld’s tanks. Let’s all honor Lolita by refusing to buy a ticket to any marine theme park and to continue to call for the development of coastal sanctuaries.