Iditarod Mushers Openly Show Cruel Treatment—What Do They Do off Camera?

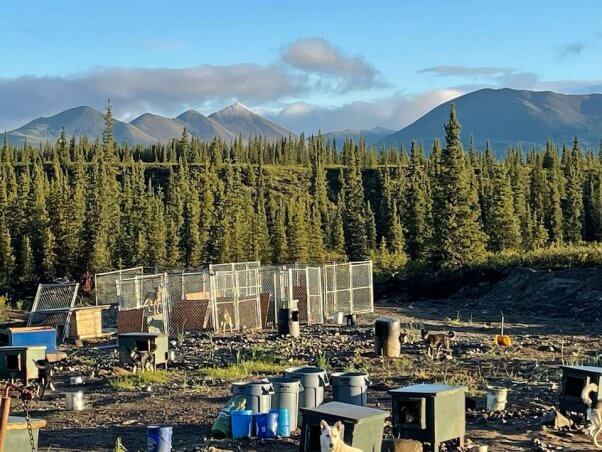

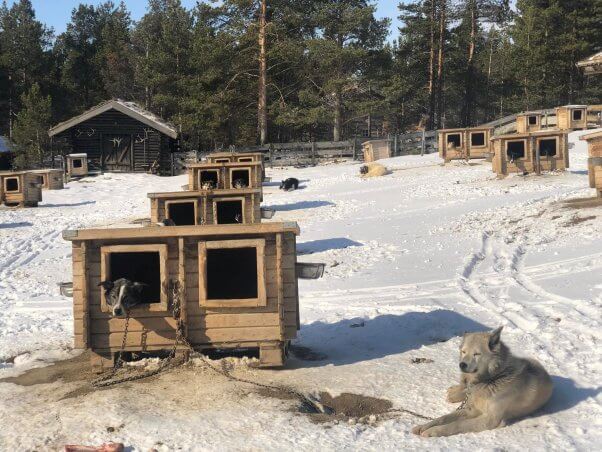

Dogs on a short chain attached to a box—that’s what you’ll see on nearly every Iditarod musher’s social media accounts. Forcing dogs to stay outside in all weather extremes is standard in the industry, and if mushers candidly post such photos publicly online, imagine what they do behind the scenes.

Iditarod Mushers’ Photos Speak for Themselves

Almost all the mushers who raced in the 2022 Iditarod either openly posted photos of their dogs chained outside or had visitors to their kennels post them. Of the nearly 50 mushers from the 2022 Iditarod, only two didn’t have photos of dogs chained up outside—and that’s likely only because they have no social media presence. In many of the images below, the dogs have carved a circle in the ground from pacing at the end of their chain or running in circles. The barking and excited tail wags are likely responses to mental stimulation they rarely get. Take a look at just some of the photos posted by mushers and see how dogs used for sledding suffer:

Jessie Holmes of Nenana, Alaska—a musher with a history of cruel “training” practices—was responsible for letting several dogs loose in a hotel parking lot after the conclusion of the 2022 Iditarod, and the dogs killed a local woman’s companion dog.

Dallas Seavey of Talkeetna, Alaska, has a record of animal mistreatment as long as the Iditarod trail itself. Dogs raced by him have tested positive for opioids, his kennel was accused of killing dogs deemed not ideal for racing, and a whistleblower reported finding dying puppies on his property.

Michelle Phillips of Tagish, Yukon, Canada, left behind five dogs during the 2022 race because they were too injured, ill, or exhausted to go on, forcing the remaining ones to work even harder.

Travis Beals of Seward, Alaska, was suspended from competing in the Iditarod for “an indefinite period of time” after being charged with assault stemming from a domestic violence incident, according to the New York Daily News. Allegedly, that wasn’t the first time he’d physically harmed his partner. Beals’ suspension lasted just one year.

Paige Drobny of Cantwell, Alaska, apparently nodded off during this year’s race while forcing her dogs to continue pulling her and her sled.

Hugh Neff of Anchorage, Alaska, was reportedly made to quit the 2022 Iditarod after the dogs he was forcing to race—described as “skinny” and apparently suffering from diarrhea—were found in such poor condition that they couldn’t continue. This notorious musher was banned from the 2019 Iditarod after he forced a dog to pull a sled until his body broke down and he inhaled his own vomit during the Yukon Quest, a similarly cruel event.

Matthew Failor of Willow, Alaska, left behind seven dogs after pushing them beyond their limits during the 2022 Iditarod. He also reportedly shot and killed a moose he encountered on the trail—a killing that surely never would have occurred had it not been for the Iditarod.

Bridgett Watkins of Fairbanks, Alaska, had four dogs who were severely injured by a moose during training before the Iditarod began. The dogs reportedly needed emergency surgery.

Richie Diehl of Aniak, Alaska, dropped his dog Jimbo from competing during the 2022 Iditarod. Jimbo reportedly escaped the “dropped dog” area in Anchorage and was on the loose for more than a day, likely scared and alone. Diehl also admitted that he had dropped out of the 2020 Iditarod because five dogs were coughing and showing signs of the beginning stages of pneumonia.

Brent Sass of Eureka, Alaska—the Iditarod “winner” of 2022—shared a disturbing video during the race of dogs covered in snow and ice in the blistering wind with, as he described, their faces “totally entrenched in snow” and their eyes “all frozen shut.”

Mats Pettersson of Kiruna, Sweden, apparently keeps his dogs in pens with holes just big enough to stick their heads through to reach their food bowls.

Chaining and Neglect Are Dog-Sledding Industry Standards

There’s no such thing as a “sled dog.” Dogs used for sledding are just like the ones we share our homes with: They love to run and play, enjoy attention and affection, and have physical limits to what they can endure. During the off-season when they’re not being forced to race beyond their capabilities, dogs used for sledding may rarely get time off their chain.

The Iditarod Runs Dogs to Their Breaking Point

By the time the 2022 Iditarod ended on March 19, nearly 250 dogs had been pulled off the trail due to exhaustion, illness, injury, or other causes.

No dog deserves to spend their days at the end of a chain or risking their lives to cart around humans. Help PETA spread the message that the cruelty of dog sledding needs to end: