Fear, Pain, and Death in a UMass Lab—This Is Anakin’s Story

On December 15, 2015, Anakin, a male marmoset monkey, arrived on a truck at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst (UMass). Along with eight other marmosets packed tightly into the same wooden crate, he was bound for the laboratory of experimenter Agnès Lacreuse.

Just a few days later, Star Wars fans would pile into movie theaters to see The Force Awakens. In the prequels, Anakin’s namesake zoomed around the galaxy, but in Lacreuse’s laboratory, the marmoset would never know such freedom. He’d spend the next four years—almost half his life—locked inside a cramped steel cage.

Anakin would never know the life that marmosets are meant to have—scampering from branch to branch in the forest, foraging for nectar and fruit with their families. His days would become a stream of bewildering tests, fear, and deprivation. And at the end of it all, he’d be killed.

Anakin’s Story

Tiny enough to perch on a finger, the monkey who would later be called Anakin was born on April 8, 2011, at a South African breeding compound for Worldwide Primates, a corporation that churns out sentient beings to be sold to facilities around the globe. He remained there for more than two years.

One day, workers stuffed Anakin into a cramped wooden crate, which was hoisted onto a cargo plane. Engulfed in darkness, he would have been able to hear the panicked shrieks of the other marmosets in the shipment—sounds that, given the animals’ profoundly social nature, would only have amplified his distress. The grueling journey by plane and truck to Miami likely took more than 24 hours.

At the Worldwide Primates facility in Florida, Anakin was known only by a number tattooed on his skin: 215. To the company, he was a piece of merchandise slapped with a barcode—property to be sold or disposed of at will.

After another two years, in December 2015, Anakin was boxed up for the more than 1,400-mile journey to UMass. The trip would be his last. Once he arrived, he’d never leave.

At UMass, he was caged alone for the first two months—unable to engage in social activities like grooming and playing, which are as vital for marmosets psychologically as food and water are for them physically. He was ultimately given a vasectomy and put in a cage with a female marmoset named Padme. But the pairing was a threadbare substitute for the rich social fabric that marmosets, like humans, need to be part of to thrive.

Through the bars of his cage, Anakin could see a male marmoset named Chewie—named for another Star Wars character—elsewhere in the room. The presence of the other marmoset, with whom he didn’t get along, made him so stressed and anxious that he developed diarrhea. But the monkeys could no more avoid each other than two puffs of air trapped in the same balloon.

To keep him still for hours at a time while they took images to evaluate the effect of aging on his brain, experimenters repeatedly restrained Anakin using a crude helmet-and-jacket system, literally bolting him to the bed of the MRI machine. Awake but unable to escape, marmosets find the banging of the MRI and the constriction of their movement so terrifying that just the “acclimation period” takes weeks.

To coerce Anakin to participate in “cognitive tests,” experimenters kept him thirsty—taking away his water for up to five hours a day, five days a week. They presented him with a touchscreen. If he complied with their wishes and interacted with the images on the screen, he received a “reward”: a small sip of liquid, an instant’s relief from his thirst. But if he didn’t comply, they locked him in an inescapable box and administered another version of the pointless test. Getting something to drink in exchange for his cooperation was no longer a possibility. At best, he could receive a dried morsel of food—devoid of any moisture that would alleviate his thirst.

Three mornings a week, in order to provide experimenters with a urine sample, Anakin was jolted from sleep, yanked from his home cage, and confined inside an empty transport box that was barely larger than a sheet of computer paper. If he peed quickly, he would be returned to the cage. Otherwise, he was trapped there for an hour. These stressful, disorienting encounters, like the “cognitive testing” sessions, were only made worse for him by human handling—an experience that marmosets typically find frightening and distressing.

In 2019, experimenters noticed that Anakin’s tail had been injured—possibly caught in a cage door that had been carelessly slammed shut. Gradually the wound healed, morphing into a scab and then a pink scar. But for more than a month, the swelling lingered.

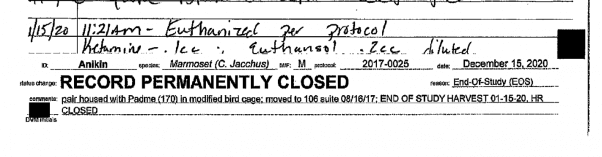

Anakin’s life of pain and deprivation finally ended on January 15, 2020, when experimenters killed him so that they could cut up and look at his brain. In death, as in life, his body was exploited for data. When experimenters were finished with him, he was discarded—tossed out like a broken test tube, no longer of use.

Marmosets Like Anakin Need Your Help

Anakin was a living, feeling being. To experimenters in Lacreuse’s laboratory, however, his life was seemingly worth little more than a data point in a journal article, a scribble on a page. He deserved to be the author of his own story, but they wrote it for him—dictating every moment, every interaction, every chance to eat and sleep.

It’s too late to change Anakin’s story—but it’s not too late to make a difference for the sensitive, intelligent monkeys just like him who are still imprisoned in Lacreuse’s laboratory. Take action to help end their suffering today.