Challenging Speciesism in English Language Arts (Grades 6–12)

In December 2018, PETA took to social media to ask people to start “bringing home the bagels” instead of the “bacon.” Judging by some folks’ reactions, you would have thought that we had opened a can of worms Pandora’s box.

With so much negativity in the world, why not use language in a way that encourages kindness to animals?

How to Teach Inclusive Language

You may cringe now when you accidentally say “kill two birds with one stone,” but the English language is riddled with conventions that reinforce speciesism, the harmful and misguided belief that all other animal species are inferior to humans. Educators must recognize that their students are picking up on things they say—for better or for worse. Trouble can arise when seemingly inconsequential conversations take on a deeper meaning in their mind and influence their view of others in unintended ways. Since we all want to instill compassion in our students, here are some easy ways to be mindful of the way you and your students think, speak, and write about animals:

Animal-Friendly Idioms

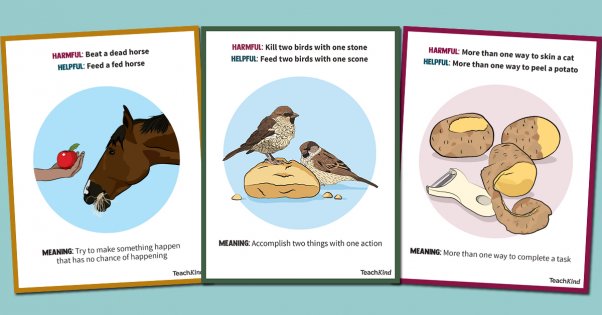

Kind people do not support dogfighting, yet many kind people use the expression “I don’t have a dog in this fight.” Many of us grew up hearing common phrases like this that trivialize violence toward animals. Other cringeworthy anti-animal phrases include “beat a dead horse” and “more than one way to skin a cat.” These old sayings are often repeated in classrooms during lessons on literary devices. While they may seem harmless, they do carry meaning and can send mixed signals to students about the relationship between humans and animals, normalizing abuse.

Instead of perpetuating these outdated and harmful phrases, use these modern, animal-friendly idioms to teach your students the importance of choosing words carefully and the power that language holds to help or hurt others. You could also have students create their own artwork depicting other animal-friendly idioms using PETA’s complete list.

Pronouns Are Important

The Associated Press Stylebook currently recommends the use of the pronoun “it” for animals who haven’t been given a name or had their sex identified by humans. This is ridiculous, considering that the billions of animals on our planet are not inanimate objects but instead have unique personalities, likes and dislikes, and the ability to feel pain and suffer. The stylebook offers “The cat, which was scared, ran to its basket,” but this language suggests that the cat is a “thing,” in the same category as the basket—not an individual with thoughts and feelings. To encourage your students to be more considerate of animals in their writing and speech, teach them to use the personal pronouns “he” or “she” for all animals (along with “they” as an acceptable pronoun for an animal of unknown sex). To practice this, you could have students read an article about animals that refers to them as “it,” highlighting all the pronouns as they go, and then have them rewrite it using only personal pronouns to refer to the animals.

Having trouble breaking the bad habit of using “it” when referring to animals? Create a classroom “It Jar“!

Redefining Language

Because Dictionary.com incorrectly defines the word “animal” as “any … living thing other than a human being,” PETA sent a letter pointing out that humans are also animals and asking the dictionary to change the word’s definitions to reflect that. Current definitions foster a divide between humans and other animals that fuels speciesism. But when it comes to fundamental feelings like happiness, pain, love, and fear—we’re all alike.

When studying connotation and denotation, have students discuss the negative connotations of words like “beast,” “vermin,” and “pest” and how they can be harmful to animals.

Metaphors and Similes

Using terms like “chicken,” “pig,” “whale,” “snake,” and “dog” as insults is a form of bullying that is harmful to humans, but it also denigrates and belittles other species, who are interesting, feeling individuals, undeserving of being viewed in a negative light. Plus, the implied assumptions about animals are often inaccurate. For example, chickens fiercely defend their young from predators—they’re not so cowardly after all. Have students create a list of common animal-related metaphors and similes (e.g., “they’re as stubborn as mules,” “stop being such a pig,” “she’s a real dog,” “I’ll be the guinea pig,” and “he was as mad as a hornet”). For each one, have them consider the following:

- What is the intended meaning of this metaphor or simile? Example: To be called a “rat” suggests that a person is disloyal.

- What evidence exists to disprove the intended meaning? Example: As experimenters have subjected rats to cruel experiment after cruel experiment, they’ve discovered that the animals exhibit empathy for one another and try to help each other out. Rats help other rats—even those who are unfamiliar to them.

- How can this metaphor or simile be reworded so that animals aren’t denigrated? Example: “Tattletale” and “snitch” are both synonyms for this use of the word “rat.”

You could also have students research metaphors and similes that celebrate animals and their abilities (e.g., “he’s as strong as an ox,” “I was as busy as a bee,” “she has a real eagle eye,” and “he’s definitely a shark”) or create their own, based on amazing animal facts.

*****

The words that we use have the power to influence those around us. We internalize their meanings—whether consciously or unconsciously—and act upon them. We now know that all animals have the ability to reason, have their own forms of communication, and can solve problems by means that we can’t always understand—yet many still suffer terribly at the hands of humans.

Unlearning speciesism takes time—so keep the conversation going with Challenging Assumptions, TeachKind’s social justice curriculum for grades 6 to 12. The lessons are designed to educate and empower students to challenge societal norms and inspire compassion and empathy for others regardless of species, race, gender, sexual identity, age, or ability.