Teaching With Film: Meet Scientists Who Choose Not to Experiment on Animals

“Don’t question why you’re killing animals—just get your degree.” Test Subjects, a documentary film from British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) Award–winning director Alex Lockwood, explores this kind of pervasive and sometimes subtle pressure on graduate students to experiment on animals—even when doing so is contrary to good science.

The 16-minute film profiles three scientists whose lives were altered when they were coached by their doctoral advisers to accept the notion that experimenting on animals was the best way to earn their diplomas—even though it was unnecessary for their research. They had all entered their graduate studies as young scientists hoping to do something to improve human health, but they soon realized that they were being taught to perpetuate an archaic system that was impeding good research—and they have since dedicated their careers to ending animal tests.

Use the following activity to help students in grades 6–12 understand the information and examine the ideas presented in the documentary. Tell students that the guiding questions for this activity are the following: “Should animals be used for experiments? Why or why not?” They should be prepared to state their positions after watching the film. You can use this activity to address these Common Core Standards in speaking and listening:

Grade 6

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.6.1.D Review the key ideas expressed and demonstrate understanding of multiple perspectives through reflection and paraphrasing.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.6.3 Delineate a speaker’s argument and specific claims, distinguishing claims that are supported by reasons and evidence from claims that are not.

Grade 7

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.7.1.D Acknowledge new information expressed by others and, when warranted, modify their own views.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.7.3 Delineate a speaker’s argument and specific claims, evaluating the soundness of the reasoning and the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

Grade 8

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.8.1.D Acknowledge new information expressed by others, and, when warranted, qualify or justify their own views in light of the evidence presented.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.8.3 Delineate a speaker’s argument and specific claims, evaluating the soundness of the reasoning and relevance and sufficiency of the evidence and identifying when irrelevant evidence is introduced.

Grades 9-10

- CCSSELA-LITERACY.SL.9-10.1.D Respond thoughtfully to diverse perspectives, summarize points of agreement and disagreement, and, when warranted, qualify or justify their own views and understanding and make new connections in light of the evidence and reasoning presented.

- CCSSELA-LITERACY.SL.9-10.3 Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric, identifying any fallacious reasoning or exaggerated or distorted evidence.

Grades 11-12

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.11-12.1.D Respond thoughtfully to diverse perspectives; synthesize comments, claims, and evidence made on all sides of an issue; resolve contradictions when possible; and determine what additional information or research is required to deepen the investigation or complete the task.

- CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.11-12.3 Evaluate a speaker’s point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric, assessing the stance, premises, links among ideas, word choice, points of emphasis, and tone used.

Divide students into six groups. Have each group watch its assigned clip, answer the accompanying discussion questions, and use their responses to prepare a brief summary of the clip to present to the class. Then have the entire class watch Clip 7: Conclusion (13:17-16:24) and answer the discussion questions as a whole group.

Group 1: Dr. Frances Cheng, Part 1 (0:00–3:32)

- Q: What childhood experiences influenced Dr. Cheng’s decision to study biology as an adult?

A: She joined a biology club in which she had the opportunity to observe animals in their natural habitat and to work in a laboratory. There, she learned that she was skilled at dissection. Adults praised her for dissecting animals well, which made her feel that a career in biology was her “calling.”

- Q: How did Dr. Cheng feel when she began her Ph.D. program?

A: She felt excited. She describes the experience as “the dream of my life.”

- Q: What was the problem with Dr. Cheng’s experiment on rats?

A: Dr. Cheng’s findings were “only true in rats but not in humans,” rendering the results of her experiment inapplicable to humans.

Group 2: Dr. Emily Trunnell, Part 1 (3:33–6:04)

- Q: How did Dr. Trunnell feel when she began her Ph.D. program in neuroscience? What did she believe about experiments on animals?

A: She felt that she was doing important work. She believed that her experiments on animals would help cure diseases and that she would only use “a few animals here and there.”

- Q: When she began experimenting on animals, Dr. Trunnell believed that there were many rules and regulations in place to protect the animals from unnecessary harm. What made her believe otherwise?

A: Dr. Trunnell found that “the rules mean practically nothing” and that scientists can do “anything [they] want to an animal,” even if their justification for their experiment is unsound.

- Q: As Dr. Trunnell advanced through the program, how did her feelings about experiments on animals change? Did she feel that continuing to perform animal tests was justified?

A: She no longer felt that her experiments on animals were for “a greater good” or to “cure any diseases” but rather felt that they were just meant to earn her a degree. She didn’t feel that this was a good enough reason to continue testing on animals.

Group 3: Dr. Cheng, Part 2 (6:05–8:07)

- Q: For what two reasons did Dr. Cheng believe that the senior scientists in her lab continued to experiment on animals?

A: She believes that they continued to experiment on animals because that’s the way they’d always done it or they thought that their experiments would eventually help humans in some way.

- Q: What did Dr. Cheng decide to do about her dilemma? Why?

A: She chose to finish her degree so that she could help animals by having “a louder voice” or more say in the scientific community about ways of handling the problem with animal experimentation.

- Q: How did Dr. Cheng’s decision affect her emotionally? Why?

A: Cheng is deeply conflicted about her decision, admitting that she still isn’t sure if it was the right choice and that she hasn’t forgiven herself for continuing her experiments on animals. She describes her actions as “selfish” and explains that it’s not human nature to kill other living beings and that experimenting on and killing animals does damage to the psychological well-being of experimenters.

Group 4: Dr. Amy Clippinger (8:08–10:04)

- Q: What does Dr. Clippinger mean when she says, “We really could be doing better”?

A: She believes that scientists could be investing their time and available funds in more human-relevant research methods.

- Q: What did Dr. Clippinger hope to achieve when she first started her studies?

A: She wanted to “[make] people’s live better and healthier.”

- Q: What does Dr. Clippinger think the scientific community is coming to an agreement upon? What does she suggest that scientists do instead of experimenting on animals?

A: She believes that scientists are beginning to realize that experiments on animals do not provide them with answers that can help humans. She suggests using human cells, human mechanisms of disease, and other human-relevant research methods to find cures for diseases.

Clip 5: Dr. Trunnell, Part 2 (10:05–11:55)

- Q: What does Dr. Trunnell say is considered “taboo” (forbidden) in the scientific community?

A: She says that it’s taboo for scientists to question whether an experiment is “right” or moral and that it’s generally believed in the scientific community that “any science is good science,” even if an experiment is poorly designed.

- Q: When does Dr. Trunnell feel that it’s necessary to “take a step back” and rethink a scientific experiment?

A: She believes that “when someone’s suffering,” a scientific experiment should be questioned.

- Q: Who did Dr. Trunnell dedicate her dissertation to?

A: She dedicated it to the more than 200 animals who died in her experiments.

Clip 6: Dr. Cheng, Part 3 (11:56–13:16)

- Q: What did Dr. Cheng’s thesis adviser tell her to take out of her dissertation presentation? Why?

A: Dr. Cheng had a line in her dissertation that said, “To all the animals that I killed, I’m sorry. I was wrong.” Her thesis adviser told her to remove this line because including it could affect her chances of graduating.

- Q: How did this make Dr. Cheng feel?

A: She says that she was hurt and disappointed about not being able to include this line in her dissertation.

- Q: How does Dr. Cheng describe the animals she experimented on?

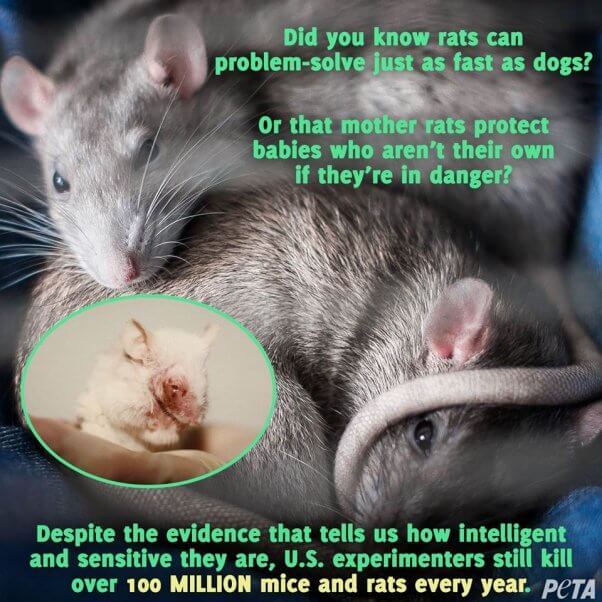

A: She viewed the animals she experimented on as individuals, not “tools for gathering my data.” She says that “they have emotions, they feel pain, [and] they suffer just the same way we do.”

Clip 7: Conclusion (13:17–16:24)

- Q: Why does Dr. Clippinger describe her current work as a “win-win”?

A: She now uses her science degree to combat animal testing and promote alternatives. She gets to save animals and protect human health.

- Q: What is significant about the number of animals Dr. Cheng has saved since graduating?

A: The number of animals she’s saved is now greater than the number of animals she killed for experiments.

- Q: Why does Dr. Trunnell feel that she’s going to be “on the right side of history”?

A: She uses her experience and expertise as a scientist to work with lawmakers to create lasting change that reduces animal suffering.

- Q: What does it mean to challenge the status quo? Have you ever taken a stand against something that was popular but that you felt was wrong? How did this make you feel? Why is it important to stand up for what you believe in?

A: When someone challenges the status quo, they object to or refuse to participate in something that’s being done simply because “that’s the way it’s always been.” Answers to the remaining questions will vary based on student experience. You could acknowledge to students that it can feel scary and lonely to stand up against something that’s popular but that we feel is wrong. It’s important to do this, though, because others may share our opinion and through a collective effort, the situation can ultimately be changed for the better.

- Q: If we know that other animals used in experiments experience pain, loneliness, and sadness, is it right to deny them the same ethical consideration given to humans?

A: Will vary based on student experience. Encourage students to consider how they’d feel if their animal companion were used in an experiment, pointing out that each year, more than 100 million animals—including dogs, cats, rabbits, hamsters, guinea pigs, mice, rats, fish, and birds—are killed in U.S. laboratories for biology lessons, medical training, curiosity-driven experimentation, and chemical, drug, food, and cosmetics testing.

- Q: Why do you think Dr. Cheng is visibly emotional throughout the film?

A: Will vary—possible answers follow. She felt sad and upset that she had hurt animals. She was disappointed that others in her community didn’t see that animal testing was harmful and ineffective. She had worked very hard and traveled a great distance to pursue a career in science but felt strongly that her studies involving animals weren’t based in science.

- Q: How would you have felt if you were one of the scientists featured in the film? Explain your answer.

A: Will vary based on student experience. Possible answers include disappointed, discouraged, and demoralized. Encourage students to consider that Dr. Trunnell, for example, was the first in her family to go to college and that Dr. Cheng left her home and family in Taiwan to study biology in the U.S. You could also remind students how each scientist featured in the film felt at the beginning of her studies.

Continue the discussion about the inappropriateness of using animals in experiments with TeachKind’s debate kit:

Debate Kit: Should Animals Be Used in Experiments?