I’ve Tried to Give My Dog a Happy Life; Marmosets Jolly and Noel Deserve One, Too

By Dr. Katherine Roe, as told to Evelyn Wagaman

December 19 is my dog Ginny’s birthday. It’s also the birthday of Jolly and Noel, two small marmoset siblings imprisoned in Agnès Lacreuse’s laboratory at the University of Massachusetts–Amherst (UMass). Like Ginny Pie Crust—who was named for my grandma Ginny and the scraps of pie crust she used to give me and her other flour-faced, sticky-fingered grandchildren to decorate at Christmastime—Jolly and Noel were given names that reflect the glad tidings of the season in which they were born. But their birthdays and their Christmassy names are where the similarities between their lives and my dog’s life end.

Ginny was born with soulful blue eyes and fur the color of caramel, the tiniest of a litter of 12 roly-poly puppies. Josie, her mother, had already been heavily pregnant when she was rescued from a hoarding situation following a call to PETA’s emergency pager that December. With no one else available on short notice to give her and her soon-to-arrive puppies a suitable home for the holidays, I had decided to make room at the proverbial inn.

Ginny was so small that she struggled to find a spot to nurse amid her squirming siblings. I bottle-fed all the puppies supplemental formula (12 babies is a lot for mama to feed on her own), but it was Ginny who needed the most care. For weeks, multiple times a day (and night), I held her warm, wriggling body against my chest, watching her bright pink tongue play peekaboo on the nipple of the bottle as she voraciously sucked in the warm, nourishing liquid. I was determined to give this small, vulnerable soul the best care I could provide.

Joyful Names but Lives of Pain

When I gave Ginny and her siblings Christmas-themed names, I was celebrating a happy occasion—12 puppies who could have been born into squalor and disease instead entered the world in a warm, loving home. To me, their story seemed to capture what the holiday season was all about. But Jolly and Noel, despite their names, don’t have a joyful story. From the day they were born, they have been prisoners in a dismal UMass laboratory.

Jolly and Noel had another sibling, who was found dead at just 11 days old. Experimenters never even gave that marmoset a name. Perhaps laboratory “living” was too much for the animal’s fragile body to take—the delicate monkeys frequently wither away and die in captivity—or perhaps staff failed to provide even the minimal level of care needed for survival. We have no way of knowing, because staff didn’t bother to record any notes about the condition of the three siblings for several days before the death.

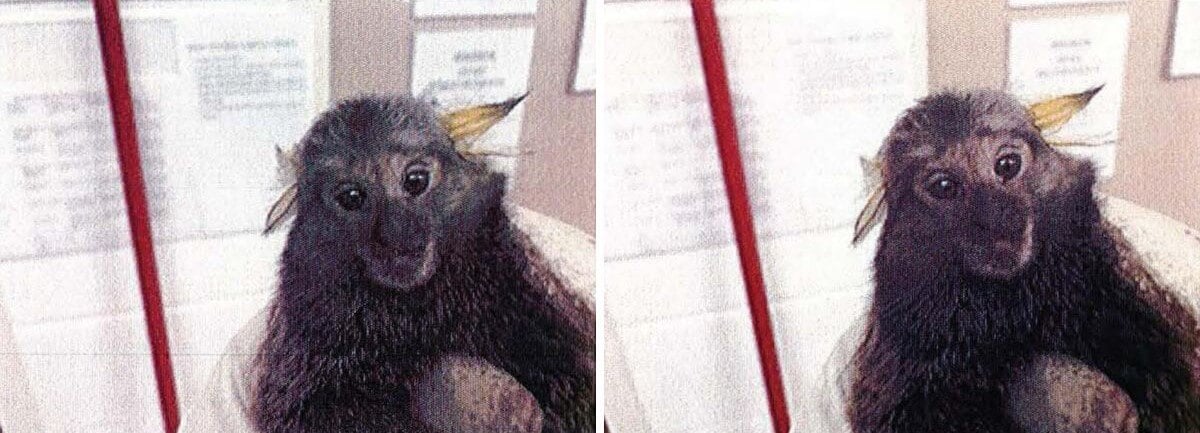

In the five years since their birth—half a lifetime for a marmoset—Jolly and Noel have lived in near-total impoverishment. They’ve never climbed a tree, seen the sky, or been part of a real marmoset family. Stacked in cramped steel cages under unnatural fluorescent lights, the profoundly social monkeys have no choice about whom to interact with and whom to avoid. After experimenters noticed a bloody wound on Jolly’s tail, they clipped the hair, only to discover a constellation of older wounds—damage likely caused by deprived, frustrated monkeys grabbing and biting it from the cage below.

In September 2022, experimenters transferred Jolly to an experimental protocol called “DHED rescue of Letrozole-induced deficits.” Marmosets on this protocol are given an experimental drug, DHED, and subjected to a battery of cognitive and “emotional reactivity” tests. They’re kept thirsty for cognitive testing so that they’ll be desperate enough to comply for just a few drops of liquid. Experimenters also force them to wear sleep-monitoring devices and press hot hand warmers—absurdly intended to induce artificial “hot flashes” associated with menopause—against their delicate skin. At the end of it all, they’re killed.

‘The Most Wonderful Time’—for Some

It’s been three years since her birth, and Ginny is now a vivacious, vocal, and deeply affectionate adult dog. She acts almost silly for a slice of banana and is so eager to play with water that she gets frantic with excitement if I even step in the direction of the garden hose. She would happily play fetch for hours and launches her entire body into the air, sleek and agile as a fox, before coming down on her favorite toy, a Kong squeaky ball. All my coworkers know her by name because she frequently pops up beside me in video calls, begging to be petted.

Sometimes I still sing to Ginny like I used to when she was just a few weeks old and in my arms, sucking hungrily on the bottle. I stroke her caramel fur and rub her in her favorite spot, the white patch of fur on her chest that I call her creamy filling. I take her for walks in nature, and I look up at the world above: the sky Jolly and Noel have never seen and the trees they have never climbed.

I know that as long as they remain imprisoned in Lacreuse’s laboratory, I can’t hope for Jolly and Noel to experience a life of contentment and playtime like the one I’ve worked so hard to give Ginny. I know I can’t hope for their birthdays to be truly happy. But for one day, at least, I hope they’re not scheduled for any invasive surgeries. I hope they’re not hungry or thirsty. I hope they’re not in pain.

It’s the least I would want for Ginny, were she in their place in a desolate UMass laboratory. But just like Ginny, they deserve so much more.

Please join me in calling on UMass to acknowledge marmosets’ right to their own lives this holiday season and all year round by finally shutting down Lacreuse’s shameful laboratory.