Experiments on Other Animals Repeatedly Fail to Find Cures for Anxiety Disorders

What Is Anxiety?

Anxiety disorders are a group of mental disorders that include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, phobias, and social anxiety disorder. These conditions are estimated to affect 264 million people worldwide.

Humans experiencing anxiety disorders often describe both emotional symptoms—such as feelings of apprehension, dread, tension, restlessness, and irritability—and physical symptoms, such as rapid heartbeat, sweating, tremors, headaches, fatigue, insomnia, and gastrointestinal issues. Many factors determine why people suffer from anxiety, including past experiences, ongoing stressful events, and brain chemistry.

Why Animal Models of Anxiety Don’t Benefit Humans

Experimenters often use mice and rats in crude attempts to study human anxiety disorders. Examples of tests used on these animals include the open field test, the light/dark box test, and the elevated plus maze or elevated zero maze. These tests measure essentially the same thing: whether an animal would rather approach or avoid spaces the experimenter thinks may scare them, such as the center of an open arena (as opposed to the walls or corners), a well-lit enclosure (as opposed to a dark enclosure), or a highly elevated platform without walls.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of “rodent behavioural tests of anxiety,” researchers found that the vast majority of tests lacked scientific validity, were not able to predict which drugs would relieve anxiety in humans, and produced highly variable results. Almost half the studies they reviewed, which involved 11,880 mice, used tests that were completely unfit for this purpose.

Life in a laboratory is always frightening for animals. They’re subjected to invasive and stressful procedures, and standard laboratory housing doesn’t meet their basic needs, which causes them to become “CRAMPED (cold, rotund, abnormal, male-biased, poorly surviving, enclosed, and distressed).” This is horrible for the animals and makes any data collected from experiments on them even more unreliable.

Some anxiety tests are severe. In the Vogel conflict test, mice or rats are deprived of water or food. Then, they’re punished with electrical shocks when they try to get the water or food presented to them. Experimenters think those who make fewer attempts to get the water or food after being shocked are more anxious. This interpretation completely ignores the fact that the shocks themselves can be anxiety-producing and that many other factors, such as learning and the state of deprivation in which the animals are kept, can affect the results of the test.

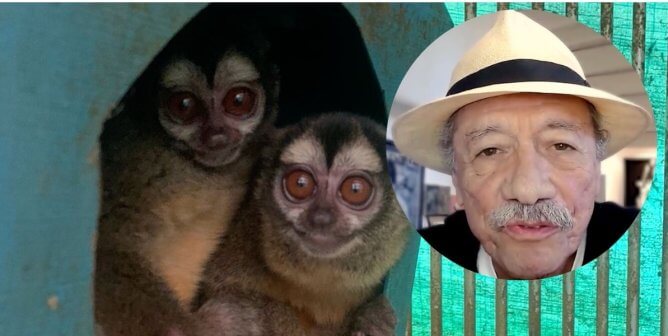

Experimenters also purposely attempt to induce anxiety in animals. They expose mice and rats to predators, like cats, either through the scent of their urine or by enticing cats to lick food off an enclosure containing terrified mice or rats.

Overall, experiments on animals have been cited as the primary source of drug failure in human neurobehavioral trials. A key reason for this is that even though other animals experience many of the same emotions we do, their brains are fundamentally different from ours in ways that are critically important in biomedical and molecular research. For example, the brain cells that communicate with each other—and the brain cells that respond to drugs meant to treat anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder—are drastically different between mice and humans.

In 2016, a Portuguese company developed a drug intended to help with anxiety, mood, and motor problems related to neurodegenerative disease. The drug was given to human volunteers as part of the Phase I clinical trial conducted by a French drug evaluation company. Six men, ages 28 to 49, experienced such adverse reactions that they had to be hospitalized. One participant was pronounced brain-dead and later died. A report on this incident reveals that “[n]o ill effects were noted in the animals, despite doses 400 times stronger than those given to the human volunteers.”

Anxiety Research Without Using Animals

Funds should be allocated to more relevant, human-based experimental models, such as advanced neuroimaging, the use of human cells for sophisticated in vitro research, and computer and mathematical modeling. For example, as part of the Human Connectome Project, researchers from a number of esteemed institutions recently used a variety of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques along with comprehensive psychological assessments of patients to map human brain circuits with symptoms of anxiety and depression, information that can be used to inform future clinical trials.

Critically, funds must also be shifted away from animal experiments and toward providing patients with greater access to mental health care and to detecting and preventing life events that contribute to the development of anxiety disorders.

For an accurate diagnosis of suicidality, depression, alcohol problems, or other mental illnesses, consult a qualified healthcare professional. If you are in crisis or think that you may have an emergency, call your doctor or 911 immediately. If you’re feeling suicidal, thinking about hurting yourself, or concerned that someone you know may be in danger of hurting themselves, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline by dialing 988. This free service is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and is staffed by certified crisis-response professionals. If you’re located outside the U.S., call your local emergency line immediately.