Smoking Experiments on Animals

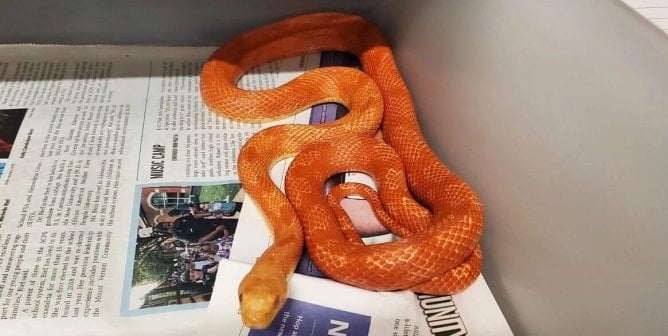

Health officials have known for decades that smoking cigarettes causes disease in nearly every organ of the human body and that animal tests are poor predictors of these effects. Yet cruel, irrelevant animal tests are still being conducted. In these tests, rats sealed in small canisters are forced to breathe cigarette smoke or vapors from electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) for up to six hours straight, every day, for as long as two years.

In the past, experimenters attached tubes to holes in dogs’ and monkeys’ necks or strapped masks to their faces to force smoke into their lungs. In other experiments, experimenters applied cigarette tar directly to mice and rats’ bare skin to induce the growth of skin tumors.

Crucial Differences

Different animals have different reactions to toxins, and animals in laboratories aren’t exposed to cigarette smoke or e-vapors in the same manner or time frame as human smokers are—making animal tests poor predictors of the results in humans.

The link between tobacco and lung cancer in humans was obscured for years because data collected from experiments on animals did not show this relationship. This isn’t surprising when you consider the biological differences between humans and other animals, such as the following:

- Rats breathe faster than humans and only through their noses, whereas humans can breathe through their nose or mouth.

- Rats live close to the ground, and their noses do a better job of filtering the air they inhale.

- A rat’s nose is smaller than a human’s nose, and therefore, a rat cannot inhale larger particles that can enter human lungs.

- The cells found in rat and human lungs differ, which affects their ability to cope with toxins.

Simply put—rats or other animals shouldn’t be used to predict what might happen in humans.

Are Smoking Experiments on Animals Required?

Belgium, Estonia, Germany, Slovakia, and the U.K. have banned tobacco product development and testing using animals.1-5

U.S. law does not have outright requirements for toxicity testing of tobacco products (including e-cigarettes) or their ingredients on animals. Manufacturers of these products must show the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) that any new products are equally or less toxic than conventional cigarettes, and they can choose what test methods to use to do so. However, the CTP may reject a company’s application that doesn’t include animal tests and suggest testing on animals in order to get a product on the market.

In addition, animal experiments to study the diseases caused by cigarette smoking is commonplace, especially at universities. For example, in 2015, a useless study conducted at three U.S. universities forced monkeys to inhale cigarette smoke for six hours every day for one year before they were killed, only to confirm that a biomarker of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was reduced—something that had been known from human COPD patients since at least 1992.6,7

The Way Forward

Instead of conducting animal tests, companies can use non-animal (computer- and human cell–based) tests and the existing body of knowledge from human epidemiological and clinical studies about the health concerns associated with smoking.

Non-animal methods overcome the species-specific differences between humans and rodents and can deliver human-relevant data. For example, three-dimensional tissue models of the human respiratory tract can be used. These tissues can be formed from cells of donors of different ages, sexes, and races as well as former or current smokers or patients with smoking-related diseases such as COPD.

To end experiments on animals, PETA funds the development of non-animal tests and PETA scientists attend and host meetings and workshops to persuade researchers and regulators around the world to end tests on animals. In addition, since the FDA was given the authority to regulate tobacco in 2009, PETA has submitted scientific comments on numerous occasions, urging the agency not to require tests on animals and allow tobacco companies to submit data from modern non-animal tests. PETA began a shareholder campaign in 2005 by filing a resolution with Altria Group, formerly Philip Morris Companies, Inc. PETA then filed shareholder resolutions with Philip Morris International and R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, calling on them to end experiments on animals. In 2013, Lorillard Tobacco Company (which R.J. Reynolds purchased in 2014) issued a policy banning all animal testing unless such tests become required by federal regulations in the future. Other companies, such as Imperial Brands and British American Tobacco, have since made similar commitments.

References

1Wallonian Government (Belgium). “Animal Welfare in Wallonia. Article D.66. 7. Accessed December 22, 2021.

2Parve V, Glasa J. National Regulations on Ethics and Research in Estonia. European Commission; 2004.

3Government of Germany. Animal Welfare Act. §7a(4). Accessed December 22, 2021.

4Glasa J, National Regulations on Ethics and Research in Slovak Republic. European Commission; 2004.

5Home Office. Guidance on the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Chapter 5, Sec. 5.23. Accessed December 22, 2021.

6Zhu L et al., “Repression of CC16 by cigarette smoke (CS) exposure,” PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0116159.

7Bernard A et al. “Clara cell protein in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage,” Eur Respir J. 1992;5(10):1231-1238. Accessed December 22, 2021.