Chimpanzees in Laboratories

Our Closest Living Relatives

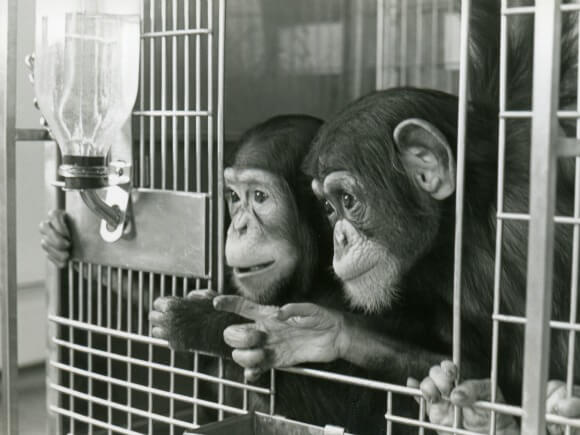

In their natural homes in the wild, chimpanzees—humans’ closest living genetic relatives, who are more like us than they’re like gorillas—are never separated from their families and troops. Profoundly social beings, they spend every day together exploring, crafting and using tools to solve problems, foraging, playing, grooming each other, and making soft nests for sleeping each night. They care deeply for their families and forge lifelong friendships. Chimpanzee mothers are loving and protective, nursing their infants and sharing their nests with them for four to six years. They have excellent memories and share cultural traditions with their children and peers. They empathize with one another and console their friends when they’re upset. They help others, even at a personal cost to themselves. They grieve when their loved ones pass away. They laugh when they’re enjoying themselves and grimace when they’re afraid.

History of Chimpanzee Use in U.S. Laboratories

Sadly, in the early 1920s, experimenters in the U.S. began purchasing baby chimpanzees who had been kidnapped from the forests of Central and West Africa. To capture baby chimpanzees, hunters would kill the mother chimpanzees and any other adult chimpanzees who tried to defend the babies. Often, whole families were killed just to obtain a few babies. The mortality rate among these babies during capture and transport was high. Those who made it to U.S. laboratories suffered terribly and died young. In 1923, the notorious American psychologist Robert Yerkes—who dreamed of creating the ideal chimpanzee “servant of science”—purchased a young bonobo and a chimpanzee he hoped to study into maturity. Both died within a year. Undeterred by the carnage and suffering inherent in the chimpanzee trade, experimenters continued to fuel the practice. In the early 1950s, the U.S. Air Force secured the capture of 65 young chimpanzees from Africa for use in military flight experiments at Holloman Air Force Base in Alamogordo, New Mexico. The descendants of these chimpanzees were used in infectious disease experiments and high-velocity seat-belt tests.

Chimpanzee Experimentation in the U.S. in the 21st Century

In 2010, the European Union passed a ban on great ape experimentation, but the U.S. continued to conduct invasive experiments on chimpanzees. At that time, there were more than 900 chimpanzees languishing in U.S. laboratories, with as many as 80 percent of them simply warehoused because there was no longer a need to use them in experiments.

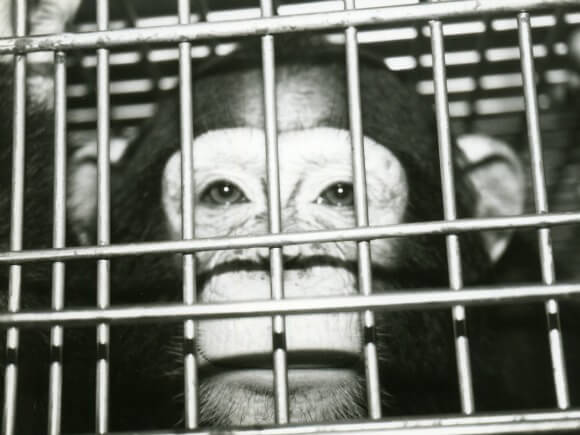

In these prisons, chimpanzees were frequently caged alone and deprived of the freedom, autonomy, and meaningful social interaction essential to their well-being. There were no families, no companions, no grooming, and no nests. There were only cold, hard steel bars and concrete—and terror and loneliness that went on for so many years that most chimpanzees would sink into depression, eventually losing their minds. As a result of enduring the terror and pain of having their bodies routinely violated for experiments and the loneliness of their tiny steel and concrete prison cells, many chimpanzees bear lifelong emotional scars. Numerous studies have shown that even long after they’ve been retired from experimentation, many chimpanzees exhibit abnormal behavior indicative of depression and post-traumatic stress. They suffer from symptoms such as social withdrawal, anxiety, and loss of appetite. They pull out their own hair, bite themselves, and pace incessantly.

Most chimpanzees in U.S. laboratories were intentionally given diseases—such as HIV, hepatitis, cancer, respiratory viruses, malaria, and heart disease—even though advances in technology made these procedures irrelevant and decades of experimentation determined that chimpanzees’ bodies do not react in the same way to these diseases as humans’ do.

In 1995—after hundreds of chimpanzees were bred in laboratories in the 1980s and ’90s on the heels of the AIDS crisis—the National Institutes of Health (NIH) imposed a moratorium on the breeding of chimpanzees when it was discovered that they don’t get sick from HIV infection and don’t contract AIDS.

In 2011, four facilities funded by NIH—including the Southwest National Primate Research Center, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s New Iberia Research Center, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and the Yerkes National Primate Research Center—continued to conduct experiments on chimpanzees. Experimenters at Yerkes subjected chimpanzees to neuroimaging, cognitive and motor testing, and invasive endocrine status tests in long-term studies on aging. At Southwest, MD Anderson, and New Iberia, chimpanzees were subjected to multiple procedures, such as, among other things, liver biopsies and frequent “knockdowns,” in which they were traumatically shot with a tranquilizer dart gun. At MD Anderson, chimpanzees were also used in an absurd experiment that attempted to determine whether salt intake increases blood pressure—something that has been well-established in humans for decades.

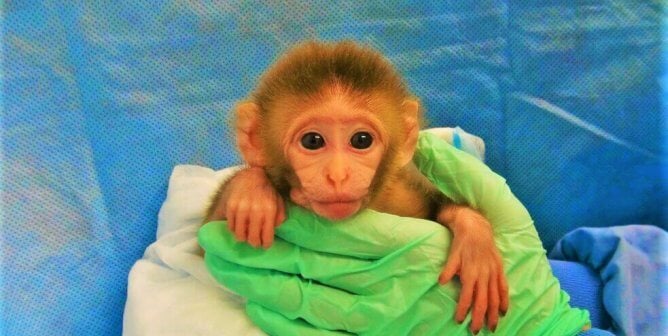

Chimpanzees were also imprisoned in commercial laboratories. Pharmaceutical giant Merck infected chimpanzees with hepatitis C and subjected them to invasive liver biopsies and blood work. A contract testing laboratory called BIOQUAL (formerly known as SEMA) tormented them in NIH-funded experiments on hepatitis C and placed swarms of mosquitoes on them to infect them with malaria. After learning that BIOQUAL was separating young chimpanzees from their mothers, locking them in individual cages, infecting them with norovirus—which causes diarrhea, vomiting, and stomach pain—and then subjecting them to months of painful biopsy procedures, PETA purchased stock in the company to urge it to phase out the use of chimpanzees and called on NIH to cut funding for the experiments. Just six months after PETA purchased the BIOQUAL stock, the company announced that it was ending all its chimpanzee experiments.

Turning the Tide on Chimpanzee Use in U.S. Laboratories

In 2011, a landmark report by the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) that examined the scientific validity of experiments on chimpanzees concluded that “most current biomedical research use of chimpanzees is not necessary.” A 2013 NIH report confirmed that experimentation on chimpanzees is unnecessary and that “research involving chimpanzees has rarely accelerated new discoveries or the advancement of human health for infectious diseases.”

In light of this damning evidence, NIH announced that it would cut funding for the overwhelming majority of invasive experiments on chimpanzees and would retire the majority of NIH-owned chimpanzees to sanctuaries. In 2015, citing a “complete absence of interest” in experimentation on chimpanzees, the agency announced that it would retire all federally owned chimpanzees to sanctuaries. This announcement followed a decision by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to classify all captive chimpanzees as “endangered,” effectively ending invasive experiments on chimpanzees.

These are historic developments, but few chimpanzees have actually been transferred from laboratories yet—and many have died while waiting. Please join PETA and members of Congress in asking NIH to send these chimpanzees to a sanctuary now!