UPDATE (January 23, 2015): Victory! Following a PETA campaign to expose and end cruel and archaic sound-localization experiments on cats at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the embattled laboratory has closed its doors for good and released several cats. See PETA’s blog post for more details.

***

For decades, countless cats have been imprisoned, cut into, and killed in cruel and useless “sound localization” experiments at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (UW).

When PETA learned that UW experimenters took photographs to document this abuse, we demanded that the school release the photos. Knowing that the public would be outraged if the truth came out, UW fought to keep its cruelty a secret for more than three years, but a successful PETA lawsuit compelled the university to release the images. PETA has now obtained dozens of disturbing never-before-seen photographs showing the miserable life and death of a beautiful orange tabby cat named Double Trouble, who was tormented for months in these experiments.

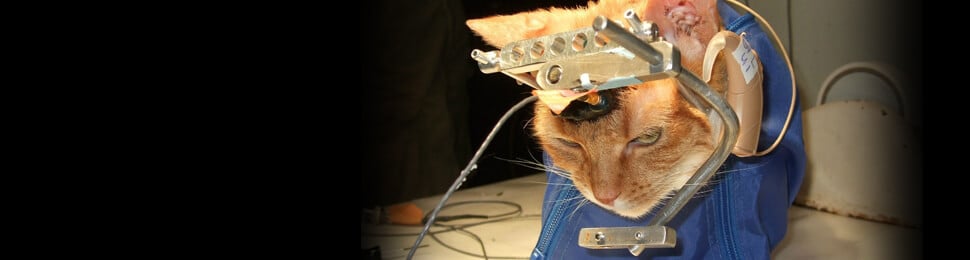

According to records obtained by PETA, Double Trouble was subjected to invasive surgeries on her ears, skull, and brain. In the first operation, a stainless steel post was screwed to her skull so that her head could be immobilized during experiments. In the next surgery—which is depicted in the photographs—experimenters cut into her head and skull and then applied a toxic substance to her inner ears in order to deafen her. Experimenters also implanted electrical devices deep inside both of her ears during this surgery.

Records show that Double Trouble’s anesthesia wore off during this surgery and she woke up to what was likely a painful and horrifying experience as experimenters were cutting into her head and skull. Another cat in the same laboratory also woke up in the middle of a similar surgery.

Following the surgeries, Double Trouble was subjected to experimental sessions in which her head was bolted in place and she was restrained in a nylon bag and forced to listen to sounds coming from different directions. Double Trouble was deprived of food for several days before these sessions in order to coerce her into cooperating in exchange for a morsel of food.

Double Trouble’s health rapidly deteriorated. Records say that she was observed twitching, which the clinical notes indicate was a “neurological sign.” Her face became partially paralyzed and the head wound that experimenters created during surgery also never healed. More than three months after her last surgery, the records describe her wound as “open, moist w/bloody purulent discharge, [with] moderate swelling.”

An antibiotic-resistant bacterial infection resulted from Double Trouble’s wound, but experimenters still forced her to endure almost two months of this misery. One of the last entries in Double Trouble’s records states that she “appear[ed] … depressed.” In the end, experimenters noted that she was too ill to continue and that the device they had implanted did not work, so she was killed and decapitated so that her brain could be dissected. A former UW-Madison veterinarian who oversaw the treatment of Double Trouble and other cats used in this laboratory recently issued a letter confirming this abuse, stating that many of the cats “suffered unnecessarily.”

Experimenters justified the use of 30 cats per year not by saying that the experiments would lead to improvements in human health but rather by stating that they needed to “keep up a productive publication record that ensures our constant funding.”

However, no peer-reviewed papers have been published in any scientific journals as a result of the suffering that Double Trouble endured. Correspondence between UW experimenters and their collaborators acknowledge that there was a problem with Double Trouble’s surgery. The experiment was a failure.

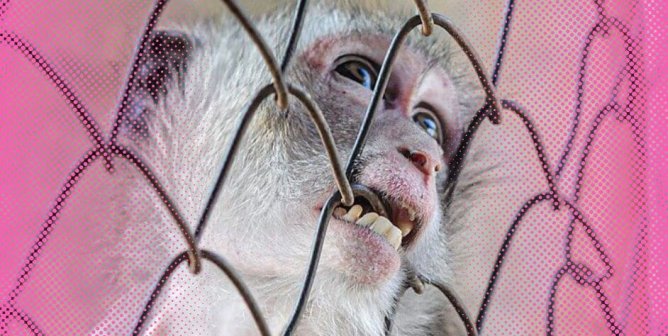

Prompted by a complaint from PETA, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) inspected this UW laboratory and confirmed that there was “a pattern of recurring infections” and that all the cats profiled by PETA in its complaint had been “diagnosed with chronic infections.” The USDA noted that some cats have died from the infections and that one cat named NJ even had to have her eye removed after an implanted metal coil caused a severe infection. As a result of this investigation, the USDA also cited and fined UW for violating the Animal Welfare Act because a cat named Broc was burned so badly with a heating pad that she required surgery. A separate report by the National Institutes of Health in response to PETA complaints found that UW did not take proper steps to avoid and provide treatment for infection in the cats’ festering open head wounds and that the university’s justification for the use of cats and the number of cats used was inadequate. The agency took the extraordinary step of ordering the laboratory to halt all invasive experiments for six months and implement major reforms.

This cruel and useless experiment is part of a larger ongoing project that has received more than $3 million in tax money through the National Institutes of Health—even though the experimenter leading the project has admitted that “our goal is not to produce a clinical treatment or a cure” and even though researchers at other institutions around the world are already using modern methods with human volunteers to investigate how the brain locates and processes sound.